New York City especially felt the blow. With a population of about 800,000 during the Civil War, New York was a place of constant recruitment, and by the summer of 1863, continual conscription. It was also the place of a large immigrant populace – especially the Irish, who were mostly laborers with little money and little hope to escape the insistence of the draft. To make matters worse for Abraham Lincoln and his determination to keep soldiers fighting in the fields, New York was largely a Democratic stronghold. Many local leaders were against Lincoln, opposed to the war, and did not care if the South seceded or if slavery continued. Governor Horatio Seymour considered the draft unconstitutional, and promised the people that he would disobey it. Yet, when the need for more soldiers arose, he reneged on his promise and allowed the draft to take place.1

Anti-war Democrats told the Irish, German and other members of the proletariat that they were merely “cannon fodder” for the bloodthirsty Lincoln Administration.2

At the beginning of the war, there were many thousands of volunteers for the Union effort. However, as the conflict continued and deaths piled high, volunteering began to ebb. As a result, the Federal Conscription Act was passed by Congress in March 1863. To make matters worse, any man of fortune could pay three hundred dollars to pay for another to take his place, making the Conscription Act a burden on the working class. The new law also specified “able-bodied male citizens” subject to the draft, exempting blacks, who were not citizens. These exemptions further angered those who felt they had given enough to the war effort. They felt it was “a rich man’s war, a poor man’s fight.”3

The smoldering disagreement grew to a white heat when news of the Union losses at the Battle of Gettysburg reached across the nation. While the South had suffered heavier casualties and the Union had won the fight, it made little difference to those who had lost a loved one – and they were many.

On the weekend after the Fourth of July, Democratic leaders and Copperheads (northern citizens who favored the Confederacy) worked to agitate the immigrant laborers in the expansive city, talking to them at the workplaces, as well as their pubs and hangouts. Women and children were not exempt from their incendiary arguments, as the anti-war people urged them to rise up against the draft.

Among Lincoln’s private papers, that were not made public until after his death, was found this missive he had written: “There can be no army without men. Men can be had, only voluntarily, or involuntarily. We have ceased to obtain them voluntarily; and to obtain them involuntarily, is the draft.”4

The high price of war was all too evident for the suffering populace around the country. The Irish in the boroughs of New York City were aghast at the numbers of their countrymen who fell at Gettysburg. The Irish Brigade, which comprised five regiments – three from New York City alone – had already fallen in enormous numbers from previous battles. Already the size of a regiment at Gettysburg rather than a brigade, the Irish Brigade had taken heavy casualties. When their families in New York learned of their losses, they were understandably distressed and angry. While the wealthy in their Lexington Avenue mansions sat out the war, the poor were losing their rising generation.

These events contained all the ingredients for an explosive outcome.

On Monday morning, July 13, 1863, as the draft offices prepared to open, hordes of working-class people, both men, women, and youth, stormed the offices and attacked the agents. They hurled rocks, brandished knives and clubs. Some carried guns. They set fire to the offices, then turned to damage more.

The mob could not be stopped because so many of the city’s police had enlisted and were fighting the war. Only a small number of police were present, and were no match for the growing crowds. The New York Times reported: “for hours a mob, embracing thousands, raged at its full bent through an extended section of our city, with arson and bloody violence. The absence of nearly our entire military force, in their great patriotic work of adding to beat back the invaders of Northern soil, gave these public enemies a rare opportunity.”5

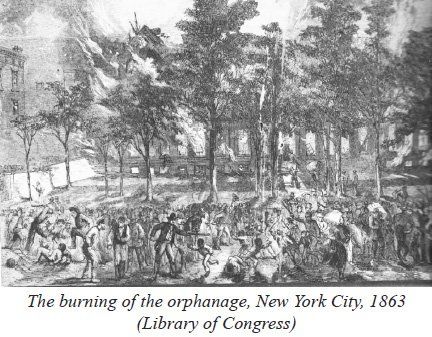

The riots continued for several days. After beating police officers and burning the draft offices, the growing mob turned on innocent black civilians, killing many. They burned an orphanage for black children – while the children were inside. Fortunately, with help the children escaped. The criminal element from neighboring cities, such as Philadelphia and Boston, made their way to New York and joined the throng in its destruction, swelling the crowd to nearly 12,000 people. The police chief was beaten, a militia leader was killed, a black cripple was flayed and hanged. The following day eleven more black men were murdered.6

A journalist reported that one of the victims was “attacked by a crowd of about 400 men and boys, who beat him with clubs and paving-stones until he was lifeless, and then hung him to a tree…Not yet satisfied with their devilish work, they set fire to his clothes and danced and yelled and swore their horrid oaths around his burning corpse. The charred body of the poor victim was still hanging upon the tree at a late hour last evening.”7

Funerals for fallen New York generals and commanding officers from Gettysburg, such as Generals Stephen Weed and Samuel Zook, were disrupted because of the destruction. Newspapermen sympathetic to the Union and Lincoln – like Horace Greeley of the New York Tribune – were also marked for attack. Greeley barely escaped the mob with his life by exiting through a side door of his office. Noted abolitionists of the city were also targeted.8

As troops from the recent battle of Gettysburg hurried to New York City to quell the riots, local leaders appealed to Irish Archbishop John Hughes, who at age 66 was seriously ill with Bright’s Disease. An ally of Lincoln, Hughes had been instrumental in helping Thomas Meagher recruit the famed Irish Brigade. Eager to erase the stigma attached to Irish Catholics at the time, Hughes was distraught to see his parishioners act in such a way. Unable to stand because of his illness, he sat, encouraging the crowd to stop rioting. Five thousand listened to him.9

While Irish workers had started the protest, they were by no means the only instigators. Like any giant mob, once law and order had vanished, criminals of all types played a role in the murders and destruction. Said one contemporary, “ The issue is not between Conscription and no-Conscription, but between order and anarchy. The question is not whether this law shall stand, but whether law itself shall be trampled underfoot.”10

On July 16, several hundred troops from the recent battle in Pennsylvania arrived in New York City and soon stopped the unrest. When members of the mob hurled stones at them, they fired upon the crowd, killing twelve. The mob then dispersed and the unrest was at an end. The instigators were soon arrested, and one of the reporters of The Tribune went to Washington to consult Lincoln about what to do with them.11

Lincoln said, “You have heard of sitting on a volcano. We are sitting upon two; one is blazing away already, and the other will blaze away the moment we scrape a little loose dirt from the top of the crater. Better let the dirt alone…One rebellion at a time is about as much as we can conveniently handle.”12

The destruction that resulted from the New York riots was immense. Rioters had closed businesses. Buildings, including industrial, commercial, government buildings and privately owned homes, were burned. Hundreds of people had died.13

The U.S. learned a difficult lesson with the terrible unrest in New York City. From that point onward, ten thousand militia were stationed in New York to prevent a repeat of the riots.14

Another terrible truth that resulted from the rebellion in New York City was that, in spite of the Union victories at Gettysburg and Vicksburg – which were the turning points in the terrible war – the war was not even close to being at an end. More sacrifice was coming. While the Battle of Gettysburg indirectly played the role of catalyst for the tinder box that was New York City in the summer of 1863, the town would also play a pivotal role in quelling the rioting there, and keeping it at bay for the rest of the war.

The New York riots were undoubtedly on Lincoln's mind for months afterward, including as he prepared his address for the dedication of a cemetery at Gettysburg. His speech galvanized the North, reminding them that the war was not for just rich or poor but for all the people. There were never again riots in major cities in the North for the duration of the war.

The horrific anarchy in New York marked a dark chapter of Civil War history. While the Battle of Gettysburg certainly played an unwitting role in its inception, veterans from the battle also played a significant part in its demise.

Sources: Adams County Star & Sentinel: “Calvin Gilbert on his 88th Birthday”, 9 April, 1927. Calvin Gilbert Family File, Adams County Historical Society (hereafter ACHS). Calvin Gilbert Family Tree, Ancestry.com. Calvin Gilbert Death Certificate, ACHS. “The History of Adams County”, ACHS, 1886 (reprint, 1992). Obituary, Calvin Gilbert, The Gettysburg Times, 14 September 1939. The Star & Sentinel, 27 August, 1938.

End Notes:

1. Gettysburg Times, 14 Sep., 1939.

2. History of Adams County, p. 354.

3. Calvin Family File, ACHS.

4. Gettysburg Times, 14 Sep., 1939, Star & Sentinel, 9 Apr., 1927.

5. Calvin Gilbert Family Tree, Ancestry. com.

6. Star & Sentinel, 27 Aug., 1938.

7. History of Adams County, p. 354. The GAR stands for Grand Army of the Republic, the association of Union war veterans who served the Union.

8. Star & Sentinel, 9 Apr., 1927.

9. Ibid.

10. Star & Sentinel, 27 Aug., 1938.

11. Gettysburg Times, 14 Sep., 1939.

12. Gilbert Death Certificate, ACHS. Gettysburg Times,

14 Sep., 1939.