The Scholarly Soldier

by Diana Loski

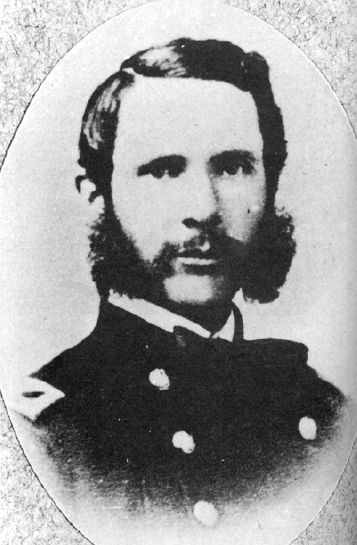

Colonel Patrick O'Rorke

(US Army War CollegeHistory Center, Carlisle, PA)

The people of Ireland today are proud of their involvement that led to victory for the Union in the American Civil War. Many of their countrymen emigrated to the United States during the 1830s and 1840s due to the drastic Irish Potato Famine; some settled in the industrious North and others to the agrarian South.

Among them was the Patrick and Mary O’Rorke family, who disembarked in Canada in 1837. Patrick and his wife Mary had six children when they made the arduous voyage across the Atlantic to escape starvation. Their youngest, Patrick Jr., was just one year old when the voyage was made.

Patrick O’Rorke Jr. was born in County Cavan, in what is now Northern Ireland, on March 28, 1836. While still a baby when the crossing was made, the young child settled with his family for several years in Canada, near Lake Ontario. In 1842, the family crossed into the United States, settling in Rochester, New York.1

Living among a large Irish immigrant population in Rochester, Patrick showed great promise, as he “was distinguished as among the brightest pupils in the public schools.”2

Tragedy struck when Patrick was just fourteen years old. His father, who worked as a laborer at the Rochester/Syracuse Railroad, was killed in an accident while on duty. His death left his widow destitute. Patrick’s older siblings had already grown, but Patrick took upon himself the care of his grieving mother. Upon graduation at age 16, he was offered three scholarships to institutions of higher learning, but Patrick declined them all. Needing to assist his mother, he worked as in masonry and marble cutting to support her. He also hoped to earn enough to marry his childhood sweetheart, Clara Bishop, who was almost exactly one year younger.3

Marriage plans were postponed when Patrick O’Rorke received a coveted appointment to West Point. His mother insisted that he accept, as Patrick’s scholarly attributes were recognized by most of Rochester. At age 21, O’Rorke was older than most of his fellow cadets, which included future Civil War compatriots George Armstrong Custer and Alonzo Cushing. O’Rorke’s intellect captured the attention of his math teacher, Gouverneur Warren, who was duly impressed with the scholarly young man. O’Rorke graduated at the top of his West Point Class in 1861 – just as the war erupted between the North and South.4

O’Rorke saw action at First Manassas, serving on the staff of General Daniel Tyler, commander of the First Division of McDowell’s army. Patrick was hotly engaged in the fight, and had his horse shot from under him. He miraculously escaped the battle without a scratch as he was surrounded by the fallen. He wrote about the battle to his brother, Tom, and remarked, “I don’t think I shall ever be shot.”5

Following the Union defeat at Manassas, O’Rorke was sent to work on the defenses of Washington, D.C. and to construct batteries on Tybee Island, near Fort Pulaski, near Savannah, Georgia. He showed a great aptitude for the task, displaying “a rare skill and talent as an engineer.” He readily accepted a position in reconnaissance, as he chafed at the inactivity in Georgia. He engaged in secret missions, at times away for weeks on assignment. He ascended a hot air balloon to scout out Confederate positions. He was instrumental in the Union capture of Fort Pulaski, which ended blockade running around Savannah. The surrender earned O’Rorke a promotion to captain on March 15, 1862.6

In July 1862, Patrick was given a short furlough. He returned to Rochester and married Clara Bishop.7

While at home, Patrick caught the attention of New York statesmen who were answering Lincoln’s call for additional troops. A new regiment, the 140th New York Infantry, was being raised, and many thought that the young officer was perfect for the role of command. O’Rorke accepted the promotion to colonel and became the commander of the new regiment. The unit became part of General Meade’s Fifth Corps, and the brigade commander was none other than O’Rorke’s old math teacher from West Point, Gouverneur Warren.8

The new regiment was organized too late to fight at Antietam, but they were present at the Battle of Fredericksburg. While not sent into the fight, they were under fire, and some of the 140th suffered casualties. The next battle, with a new commander of the army to lead them – General Joe Hooker – General Warren was placed on Hooker’s staff. He recommended O’Rorke to command the brigade, which he ably did. The men of the 140th were proud of their colonel’s promotion. It was short lived, however.

Politics dictated who was permanently promoted in the field, and an artillery commander, Stephen Weed, who had served with much distinction during the Peninsular, Second Bull Run, and Antietam campaigns, was seeking a chance to move up in the ranks. The infantry was the natural place for promotions, as more men were fighting there, and more were killed or wounded in battles than those in the artillery. Since O’Rorke was the newest infantry brigade commander in the corps, Weed took over the brigade and Patrick was relegated back to command his regiment. A true soldier, Patrick never complained.9

After the next battle, it mattered little anyway.

O’Rorke requested a short leave of absence in June to meet his wife in Baltimore. The pair had hardly commenced on their married life together as the war had interrupted it. He returned to the Army of the Potomac as the troops marched northward from Virginia, following General Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia into Pennsylvania. On June 26, the troops learned that George Meade had replaced General Hooker as commander of the Union army. A few days later, the two armies collided at Gettysburg.

The Battle of Gettysburg began on July 1, 1863. The Fifth Corps, now led by General Sykes, did not reach the outskirts of the borough until July 2 – after a restless march in high heat and little rest. The night before arriving at Gettysburg, O’Rorke lay beside one of his men, but could not sleep. Captain Leeper, who shared the groundcloth with the colonel, remembered that the colonel “seemed to have foreboding anticipations.”10

The 140th New York was held in reserve along the Baltimore Pike south of town. While they rested for a few short hours, a missive from General Meade reached the troops, and many commanders read them to the men. Meade’s circular “authorized the execution of malingerers” as every man was needed in the fight. O’Rorke, who rode a small brown horse, was wearing a “soft hat”, military cape and white leather gauntlets. As his aide, Porter Farley read the missive, O’Rorke addressed his regiment: “If there is a man this day who is base enough to leave his company, let him die in his tracks. Shoot him down like a dog.”11

The men of the Fifth Corps did not wait long before they were called to the front. Earlier that day, General Sickles of the Federal Third Corps – who was antagonistic to General Meade as Sickles was a close friend of the recently deposed Hooker – moved his entire corps away from the Union defensive line and deployed them a half-mile to the front. As a result they were exposed and with large gaps in the lines. The Confederates quickly saw an opportunity, and attacked Sickles, forcing his men back. The move also left the Union’s left flank, Little Round Top, without fighting troops. The situation was indeed dangerous for the Federals. Were the men in gray to reach Little Round Top, the entire Union line was in danger of falling, and the men in blue were in danger of certain death or the loss of the entire army.

General Warren, who remained on George Meade’s staff after Hooker was demoted, saw the phalanx of men in blue along the Emmitsburg Road and nervously checked the Union line. When he reached Little Round Top, he was alarmed at the emptiness of the hill.

Simultaneously, Weed’s Brigade, which included the 140th New York, were ordered into the fray in the Wheatfield, where some of Sickles’ men were fighting the aggressive and determined Confederates. General Warren sent a quick note with the orders to get a regiment up to the hill. Colonel Strong Vincent and his brigade answered that call and quickly scaled the heights just before a horde of Confederates rushed into the melee.

Realizing that one regiment was not enough, General Warren saw Weed’s brigade in the valley below Little Round Top. He noticed his former math pupil leading his regiment. He galloped toward O’Rorke, calling his name over the din of battle: “Paddy, Paddy! Give me a regiment!”12

Colonel O’Rorke turned to General Warren, but hesitated. “General Weed is ahead and expects me to follow him,” he said. Orders were orders, and O’Rorke, the consummate West Point soldier, knew his duty was to follow Weed. Warren, though, was insistent. “Never mind that,” he said. “Bring your regiment up here, and I will take the responsibility.”13

O’Rorke looked at Little Round Top and instantly realized the danger. He turned his men to ascend the hill on the double-quick. They reached the apex of the hill and saw Confederates attempting to scale the western slope, opposite Devil’s Den. There was no time for formation, or to load their muskets. O’Rorke dismounted, drew his sword and called, “Down this way, boys!” The 140th followed and routed the ascending rebels. The action no doubt saved the hill in conjunction with the brave actions of Vincent’s Brigade.14

The win came with a high price. Patrick O’Rorke was struck in the neck by a Confederate bullet. He fell dead on the western slope of the hill.

O’Rorke’s body was taken to the Jacob Weikert farm behind the Round Tops, and wrapped in a blanket on the porch. His adjutant, Porter Farley, accompanied the body. He later said, “I choked with grief as I stood by his lifeless form.” General Weed’s slain body was later placed on the porch beside the young colonel. He too had been shot in the neck on Little Round Top. Lieutenant Charles Hazlett, who commanded the battery of cannon on top of the hill, was also shot dead. His body joined O’Rorke’s and Weed’s on the Weikert front porch.15

The Union forces held Little Round Top, and the valley below was filled with Confederate dead and wounded. The height had protected many of the Union troops, but there were still abundant casualties. An artilleryman in Hazlett’s Battery, Malbone Watson, was wounded in the fight. He was taken to the Weikert farm, and was placed on the porch due to the lack of room in the house. Because of the chaos of battle, Watson had not known the fate of his compatriots, and he knew O’Rorke, Weed, and Hazlett well. A brisk wind blew away the blankets that covered the three dead commanders. The shock of seeing his three friends lying together in death “nearly killed me,” he remembered.16

Clara O’Rorke, at age 25, retrieved her husband’s body from a shallow grave at Gettysburg. He was buried in Rochester with military honors. For the rest of the war, Clara remained with her parents. Like so many Civil War widows, she never remarried. In 1871, she became a nun, taking her vows at the Society of the Sacred Heart in New York. She became a Mother Superior at a convent in Detroit, and later moved in that position to Albany, New York and later Providence, Rhode Island. She died in Providence in 1893.17

General Warren lamented the death of the promising young soldier for the rest of his life. He wrote to Porter Farley, “I would have died to save him if I could.”18

Atop Little Round Top, a statue memorializing the scholarly commander is found near the spot where the young colonel fell in defense of the tenuous Union line in 1863. The monument to the entire 140th New York was dedicated there in 1889. O’Rorke, with his mutton-chop whiskers, is found in bronze on the face of the monument. At the dedication ceremony, one remembered O’Rorke as “the beau ideal of a soldier and a gentleman.”19

Had he survived the battle and the war, Patrick O’Rorke, the scholarly soldier, would undoubtedly have risen to great heights with his ability to lead and his intellectual genius. But sadly, like so many promising young men, he died far too soon. Such is the fate of wars, and those who must fight them.

Sources: Appleton, John, ed. Appleton’s Cyclopedia of American Biography. Vol. IV. New York, 1887. Bennett, Brian. The Beau Ideal of a Soldier and a Gentleman. Lynchburg, VA: Shroeder Publications, 2012. Fox, William F. New York at Gettysburg. Volume 2. Albany, NY: J.B. Lyon Company, 1902. Hawthorne, Frederick W. Gettysburg: Stories of Men and Monuments. Hanover, PA: The Association of Licensed Battlefield Guides, 1988. Letter: Patrick O’Rorke to Tom O’Rorke, Recorded by Rev. Robert F. McNamara, “Gettysburg Centenary Recalls Heroism of Rochestarian” City Catholic Journal, June 28, 1963. Norton, Oliver Willcox. The Attack and Defense of Little Round Top. Gettysburg, PA: Stan Clark Military Books, 1992 (reprint, first published in 1913. Clara O’Rorke Family Tree, Ancestry.com. Pfanz, Harry W. Gettysburg: The Second Day. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 1987. Warner, Ezra J. Generals in Blue: Lives of the Union Commanders. Baton Rouge and London: Louisiana State University Press, 1964.

End Notes:

1. Appleton, p. 620.

2. Ibid.

3. Ibid.

4. Bennett, p. 38.

5. Letter, Patrick O’Rorke to Tom O’Rorke, City Catholic Journal, 1963, pp. 18-21.

6. Appleton, p. 620.

7. Bennett, p. 63.

8. Warner, p. 541.

9. Norton, p. 40. Warner, p. 548. Bennett, p. 106.

10. Bennett, p 112.

11. Pfanz, p. 77.

12. Norton, pp. 130-131.

13. Ibid.

14. Ibid. p. 134.

15. Ibid. p. 139.

16. Bennett, p. 128.

17. Clara O’Rorke Family Tree, Ancestry.com.

18. Norton, p. 319.

19. Hawthorne, p. 55. Fox, vol. 2, p. 958.