The Winter of Discontent

by Diana Loski

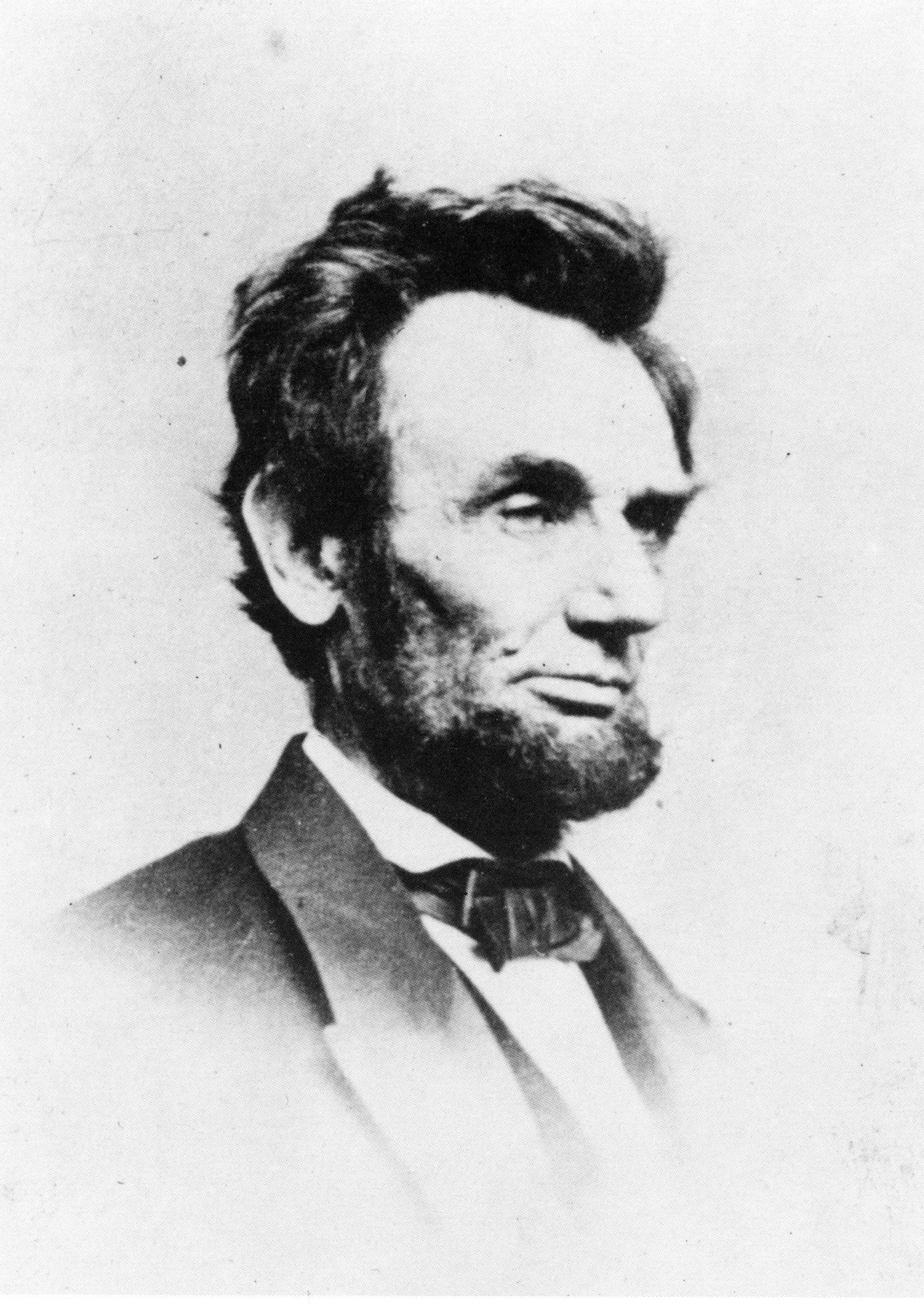

Lincoln's 1860 election caused an uproar of controversy

(Library of Congress)

Abraham Lincoln stood valiantly against the institution of slavery from his first glimpse of a person in chains. He never wavered from that stance. With his otherwise moderate views and his even-tempered manner, combined with his deep understanding of the Constitution and his firm opinions against the propagation of slavery, he not only secured the Republican nomination for President, he also won the Presidency by a significant electoral majority.

One reason for Lincoln’s election was that the Democratic party offered two candidates in 1860: northerner (and former Lincoln rival for the Illinois senate) Stephen A. Douglas and southern candidate John C. Breckinridge. The voting split significantly among the two, making Lincoln the winner.

Lincoln’s election caused an uproar in the South. Robert E. Lee, who was then still a highly respected Federal commander, remembered that “Politics had become the affair of every man and the concern of every soldier, for the old amity among the states was gone.”

1

Newspapers in the South almost immediately “told of much dissatisfaction and of many appeals for secession.”

2

Within weeks, one state, South Carolina, did indeed vote to secede from the Union, on December 20th.

Shortly after the new year dawned, more states from the South began to follow suit. On January 9, 1861, Mississippi became the second state to secede from the Union. The following day, Florida followed suit; the day after Alabama joined the group in declaring itself no longer in the United States. Before the month of January had elapsed, two more states, Georgia and Louisiana, had seceded as well.

3

When Texas joined the secessionists on February 1, the governor, Sam Houston, strongly advised against it. He resisted the claim of his state for secession from the United States, and refused to comply with it. As a result, he was promptly deposed as governor.

Lincoln, ever the optimist, answered those who were deeply worried: “My advice is to keep cool. If the great American people will only keep their temper, on both sides of the line, the troubles will come to an end.”

4

Unfortunately, factions on both sides did not keep their tempers. A Kentucky statesman, John Y. Brown, threatened that if Lincoln attempted to keep the states in the Union and protected the Federal forts – many of which in Southern waters and in danger of capture – that “[we] will spring up crops of armed men, whose religion it will be to hate you and curse you.”

Pennsylvania congressman Thaddeus Stevens replied, “Rather than show repentance for the election of Mr. Lincoln, with all its consequences, I would see this Government crumble into a thousand atoms.”

5

Abolitionist Benjamin Wade, aghast at the fever pitch throughout the nation, wrote to President-elect Lincoln, “I cannot comprehend the madness of the times…Treason is in the air around us everywhere.”

6

When Lincoln left his home at Springfield, on a gray, misty winter’s day, the day before his 52nd birthday, he thanked the townspeople who bade him farewell for their kindness. He then said, “I now leave, not knowing when, or whether ever I may return, with a task before me greater than that which rested upon Washington.”

7

Lincoln was correct, almost prophetic, on both counts. He would never return alive to Springfield, and his tenure would be the most difficult so far for any sitting President.

The railroad trip to Washington from Springfield lasted twelve days, with stops in many Northern cities on the way. There was one city en route that was filled with secessionists – the city of Baltimore. Lincoln was warned by many in law enforcement of “ threats of mobbing and violence”, “secret meetings” and men set on assassination. One man insisted on “murdering Lincoln” by “plunging a knife into his heart.” Another threatened to “blow up the trains.”

8

In order to quell the violence and protect the President-Elect from almost certain death, the itinerary was altered, and the train carrying Lincoln arrived in Baltimore at 3:30 in the morning.

While Lincoln was traveling by train to the capital city, another city held its own inauguration on February 18, 1861. Jefferson Davis was sworn in as the President of the hastily created Confederate States of America, in Montgomery, Alabama, the fourth state to secede the previous month. In his inaugural speech, Jefferson David declared that secession “was a necessity, not a choice,” and it had happened “to preserve our own rights and promote our own welfare.” In other words, to continue unfettered with the institution of slavery.

9

On March 4, 1861, Lincoln gave his first inaugural address in Washington. Still hoping to quell the anger and instill calm, he said, “In your hands, my dissatisfied countrymen, and not in mine, is the momentous issue of civil war. The government will not assail you. You can have no conflict without being yourselves the aggressors.” He continued in a conciliatory tone: “We are not enemies, but friends…the mystic chords of memory, stretching from every battle-field, and patriot grave, to every living heart and hearthstone all over this broad land, will yet swell the chorus of the Union, when again touched, as surely they will be, by the better angels of our nature.”

10

Fort Sumter was still five weeks away. In that critical month, Lincoln and his Cabinet worked to keep war at bay. There were riots in Baltimore, and Union soldiers sent to restore order were attacked. Four more states: Virginia, Arkansas, North Carolina, and Tennessee were yet in the Union but secessionists appeared to take control of the legislatures, and even level-headed Unionists in those states could not walk back the wave of disunion that crashed upon them.

Some legislators offered a Constitutional amendment as another attempt at compromise, promising that slavery would never be ended by Congress. Lincoln refused to consider it. A group of religious leaders from Baltimore came to President Lincoln, asking him to promise that he would not interfere with slavery, or to let the Confederate states depart in peace. Lincoln threw them out of his office.

11

The speech he had given in the Cooper Union Building in New York City over a year before resonated with him: “Let us have faith that right makes might, and that in that faith, let us, to the end, dare to do our duty as we understand it.”

12

As the nation crumbled around him, Lincoln was determined to do his duty – a commission given to him by the American people. That duty was to preserve the Union. And by preserving it, the first nail in the coffin of slavery was inserted.

It was a true winter of discontent. There had been too many years of uneasy compromise, too many years of turning away from the issues. A sizable minority could not fathom a Republican, anti-slavery President. The times were volatile, and it was about to get far worse. The years of careful compromise were at an end, and the winter of discontent would fade into a spring filled with war and four years of death and destruction.

Sources: Freeman, Douglas Southall. R.E. Lee . Vol. 1. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1962 (reprint, first published in 1934). Goodwin, Doris Kearns. Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham Lincoln . New York: Simon & Schuster, 2005. Lincoln, Abraham. Selected Writings . New York: Barnes & Noble, 2013. National Park Service. “War Declared: States Secede from the Union!” nps.gov . Phillips, Donald T. Lincoln on Leadership for Today . Boston & New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2017. Sandburg, Carl. Abraham Lincoln: The Prairie Years & the War Years . New York: Galahad Books, 1993 (reprint: first published in 1954).

End Notes:

1. Freeman, p. 413.

2. Ibid. p. 414.

3. “War Declared”, nps.gov .

4. Phillips, p. 97.

5. Sandburg, p. 188.

6. Ibid.

7. Ibid., p. 195.

8. Ibid., p. 204.

9. Phillips, p. 104.

10. Lincoln, p. 624.

11. Goodwin, p. 325.

12. Lincoln, p. 594.