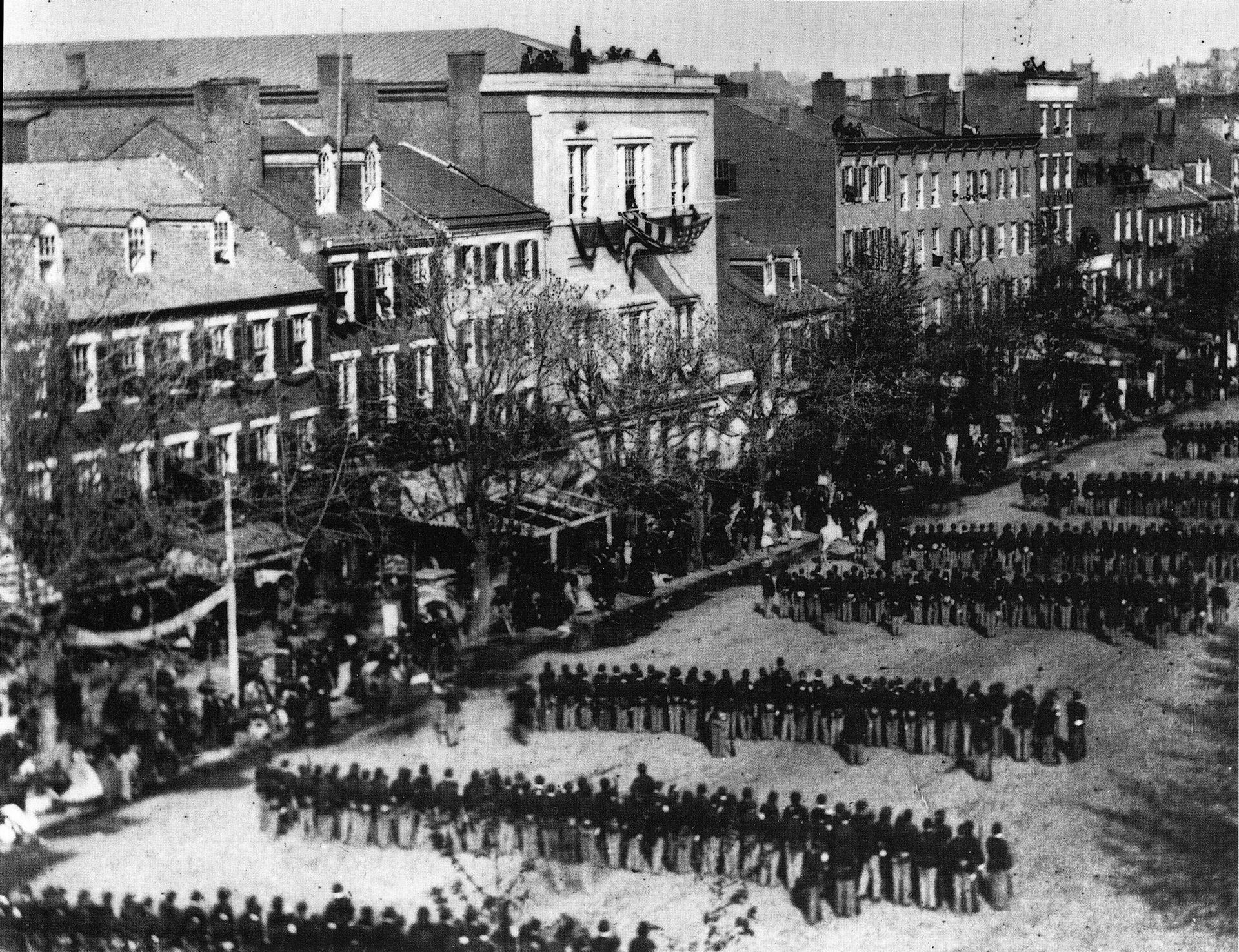

The Lincoln Funeral Procession, New York City (National Archives)

Abraham Lincoln said, in one of his early speeches, “As a nation of free men, we must live through all time, or die by suicide. I hope I am over wary; but if I am not, there is, even now, something of ill omen amongst us.” Lincoln knew, even as early as 1838 when he uttered those words in a speech, there was an issue dividing us as a people, and that issue was slavery. He was concerned that the division caused by this immoral institution would lead to civil war – which it ultimately did – and the possible end of our nation of the people.1

Most civil wars have carried on for decades and even centuries. Some nations remain divided, such as the Middle East, or Ireland from Northern Ireland, from contentions that still arouse angst; some borders continually change as wars erupt again and again over time. The English Civil War, for example, threw the nation into turmoil for decades, killing many thousands, and resulting in the execution of their king, Charles I, in 1649. His successor, Oliver Cromwell, who governed as a “protector” instead of a monarch, continued to pillage and plunder, making war to pay back the soldiers who supported him, especially in Ireland. When he finally expired, the English people were so weary of his deeds, that they asked for their monarchy to return, which it did. There is little wonder that so many during that century emigrated to the American colonies2

Monarchs and dictators rule for life, and often their acts do not reflect the will of the people. The American Revolution is a prime example of the disillusioned governed throwing off the shackles of a tyrant king – which George III definitely was. Our revolution lasted for seven years (from 1776 to 1783), and the unique peace that followed – the formation of a constitutional republic, and the agreement among leaders who were normally in opposition to each other – was almost miraculous. Comparing the American Revolution with the contemporary French Revolution – which ended in terrible bloodshed, anarchy, unfair trials and mass executions – led France to, like the English, accepting a dictator to lead them because they could not agree to lead themselves.

It is an interesting fact that, after America became a nation, other nations began to follow suit in organizing republics. In the early nineteenth century, most of the South American nations had gained their independence from Spain. Mexico and Cuba gained theirs later. Canada also was liberated from Great Britain, and although still part of the empire, it had earned the right to independent rule. Today, there are multiple republics and democracies throughout the globe. Like Lincoln had implied in his Gettysburg Address, this nation was the great experiment, and other countries were closely watching.

The Civil War was part of our greatest tragedy. At its close, there was another, darker, event that surpassed it. It was the assassination of Abraham Lincoln.

Before the Lincoln assassination, no U.S. President elected by the people had been murdered in office. William Henry Harrison had died of pneumonia one month after his inauguration, and Zachary Taylor died under unexplained circumstances after eating cherries and milk on the 4th of July in 1850. Until April 14, 1865, no President had been assassinated.

Lincoln’s murder, on the eve of the long-awaited peace, thrust the nation into a calamitous state. Perhaps the United States could die by suicide after all.

When the news reached the populace of Lincoln’s assassination, most of the Union soldiers remained in the field, and not all Confederate armies had surrendered. General Joshua Chamberlain, who commanded a Union brigade near Richmond, wrote upon hearing the news: “Heart-wrung by the sacrifice, he [Lincoln] had taken deep hold upon the soldier’s heart, stirring its many chords…It might take but little to rouse them to a frenzy of blind revenge. And right before them lay a city, one of the nerve centers of the rebellion.”3

Union generals worried that perhaps a darker spirit would take hold of the Federal soldiers, and they were equally concerned about the vanquished South. Perhaps they would rise up again. It had all happened before in history, when chaos and destruction were unleashed upon the vanquished by the victors: Count Tilly and the Swedish army had done so in 1631, when they finally broke through a German walled city at Madgeburg – and the soldiers massacred the 20,000 inhabitants. There was a similar situation when Oliver Cromwell finally overtook a stubbornly resistant Irish town in Wexford. The more recent was the destruction of the French garrison in San Sebastian in northern Spain by Portuguese and British forces led by the Duke of Wellington in 1813. The victors slaughtered the French military and hundreds of civilians, including women and children, and burned and pillaged the town, in spite of their commander’s attempts to quell them.4

Fortunately, the Union soldiers restrained themselves and acted instead in the way Lincoln would have wished. Mr. Lincoln had in his great heart ,” remembered his friend Ward Hill Lamon, “ no place for uncharitableness or suspicion…He had a sublime faith in human nature. ” He also detested war, and only reluctantly entered into it after the secession of Southern states and the attack on Fort Sumter on April 12, 1861. “Both parties deprecated war,” Lincoln said of the conflict. “But one of them would make war rather than let the nation survive; and the other would accept war rather than let it perish.”5

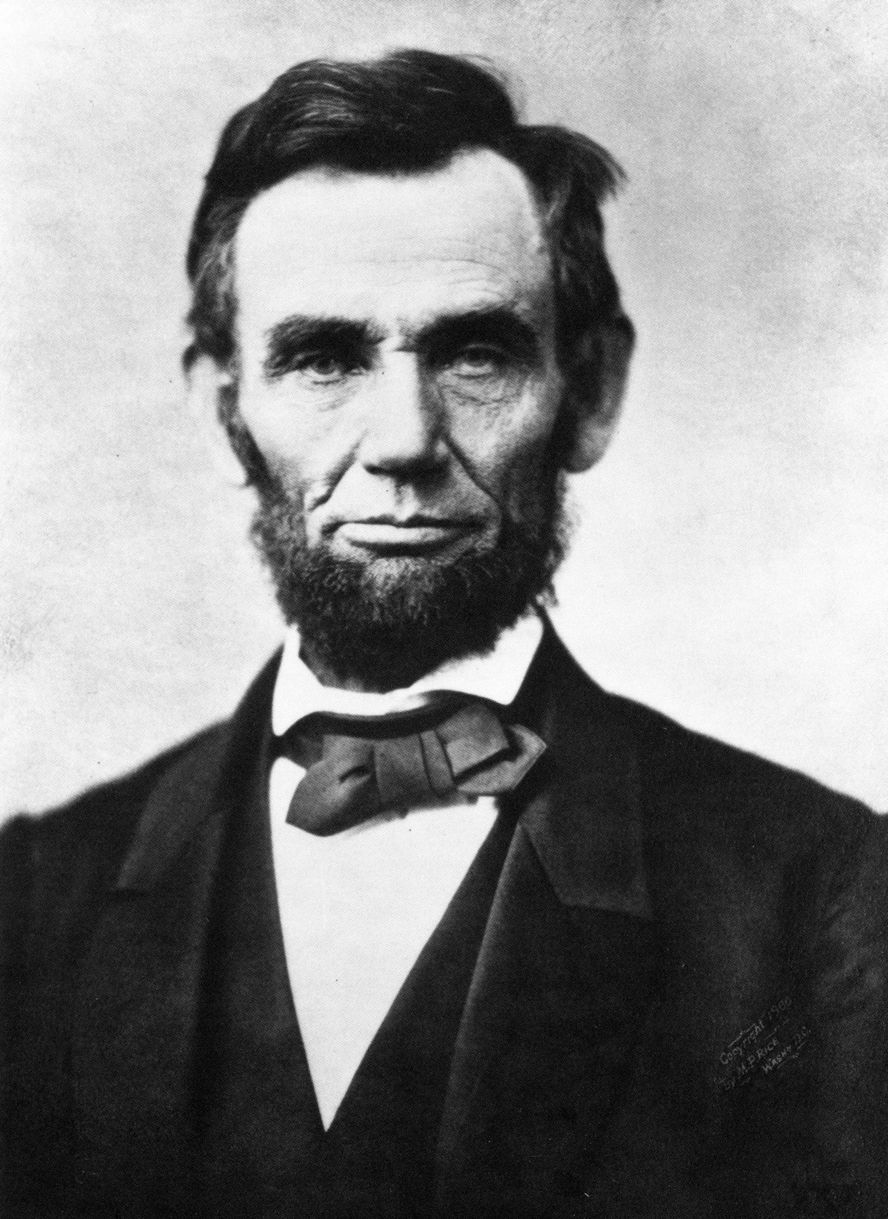

Abraham Lincoln

(Library of Congress)

The tragedy that remained, however, was that it took many years to finally accomplish reconstruction that would have occurred far sooner had Lincoln survived. Lincoln’s successor, Andrew Johnson, did not possess the leadership capabilities necessary for the office at such a time. He also proved far less magnanimous with the former Confederacy. General Chamberlain had rightly proclaimed as much to a Southern lady, who had asked him about the sudden change in their demeanor on the day the news of the assassination reached Virginia: “As I was pacing the ground…the lady of the house – there were never any men at home in those days – came out to ask what had happened…‘It is bad news for the South,’ said I. ‘Is it Lee or Davis?’ she asked, a look of pain pinching her features. ‘I must tell you, madam, with a warning,’ I replied. ‘I have put your house under strict guard. It is Lincoln.’ I was sorry to see her face brighten with an expression of relief. ‘The South has lost its best friend, madam,’ was the only thing to say.”6

“No man who knew Abraham Lincoln could hate him,” declared Frederick Douglass. There were millions who did not know him, however, and he was expressly despised by many, and blamed for the war that he had never wanted. Politicians, including General McClellan who had served under his Presidency, called him “a hideous baboon.” During the election of 1864, one Democratic delegate from Ohio said, “ They could search hell over, and not find a worse President than Abraham Lincoln.” A New York congressman ominously declared, “The people will soon rise, and if they cannot put Lincoln out of power by the ballot, they will by the bullet. 7

It was the Union soldier who gave Lincoln the victory of a second term, which proved the final nail in the coffin for the Confederacy, and ultimately for Lincoln. Charles A. Dana, who served as Assistant Secretary of War, remembered that “the political struggle was most intense, and the interest taken in it, both in the White House and the War Department, was almost painful.”8

“Mr. Lincoln believed that his career would be cut short by violence,” wrote his friend and bodyguard Ward Hill Lamon. He also remembered that the President “was a stranger to fear” and “he often eluded our vigilance.”9

It was surprising to many that the nation mourned Lincoln in the way that they did. “Instantly, flags were…at half-mast, all over the city, the bells tolled solemnly, and with incredible swiftness Washington went into deep, universal mourning.” As the procession bearing his body from the Petersen house, where he died, to the White House, a heavy rain fell on that Saturday before Easter, with crowds lining the streets on the way. “Every head was uncovered and the profound silence which prevailed was broken only by sobs and by measured tread of those who bore the martyred President back to the home which he so lately quitted full of life, hope, and cheer.”10

From the funeral in Washington to his final resting place in Springfield, Illinois, millions of people paid their respects, either by quietly filing by his casket in varied cities where he lay in state, or standing along the tracks to catch a glimpse of the funeral train. On Tuesday, April 18, the first day where the slain commander lay in state, “the largest mass of people” imaginable, lined up to pay their respects. Journalist Noah Brooks climbed the stairs to the Capitol dome to witness the line of humanity. “Looking down from that lofty point,” he wrote, “the sight was weird and memorable. Directly beneath me lay the casket…and, like black atoms moving over a sheet of gray paper, the slow-moving mourners crept silently in two dark lines.”11

In addition to the loss of such a President in such a devastating manner, the United States also lost, with the treacherous assassination, an innocence which was gone forever. The loss of Lincoln at such a pivotal time, when he was most needed for what he had termed “to bind up the nation’s wounds”, cast a pall over the still severely wounded, still divided country.12

Speaking practically, as the end of the war was in sight, Lincoln had laid out his plan for reunion: “We all agree that the seceded states, so called, are out of their practical relation with the Union; and that the sole object of the government, civil and military, in regard to those states is to again get them into their proper, practical relation…Let us all join in doing the acts necessary to restoring the proper, practical relations between these states and the Union.”13

It is for this reason that Lincoln’s assassination was America’s greatest tragedy, and one from which the nation almost did not recover.

“It’s not just merely for to-day but for all time to come that we should perpetuate for our children’s children this great and free government,” Lincoln said in an 1864 address to an Ohio regiment. “I beg you to remember this.”14

Thankfully, Lincoln lived long enough to see that hope realized.

“Lincoln was a humanitarian as broad as the world,” said Russian author Leo Tolstoy in 1908. “He was bigger than his country – bigger than all the Presidents together. We are still too near to his greatness, but after a few centuries more, our posterity will find him considerably bigger than we do.”15

At least, after his passing, people began to see just how great a leader he was. Noah Brooks wrote, “Posterity has vindicated the wisdom of Lincoln, and has dealt charitably with the errors of those who in their day lacked that charity.”16

Error, combined with an intransigent mindset among a sizable minority, who despised the 16th President, led to secession, war, and our darkest decade in the mid-19th century, culminating during a cold April weekend in 1865.

Yet, in spite of that early premonition from Lincoln’s 1838 speech, the nation survived, though he did not live to see it.

An outside view of the Lincoln tomb,Springfield, IL

(Author photo)

Sources: Brooks, Noah. Washington D.C. in Lincoln’s Time: A Memoir of the Civil War Era by the Newspaperman Who Knew Lincoln Best (edited by Herbert Mitgang). Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press, 1958. Chamberlain, Joshua Lawrence. The Passing of the Armies. New York: Bantam Books, 1993 (reprint, first published in 1915). Churchill, Winston S. A History of the English Speaking Peoples. Volume II. New York: Dorset Press, 1956. Goodwin, Doris Kearns. Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham Lincoln. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2005. Holzer, Harold. President Lincoln Assassinated! The Firsthand Story of the Murder, Manhunt, Trial, and Mourning. New York: Literary Classics of the United States, Inc., 2014. Lamon, Ward Hill. Recollections of Abraham Lincoln. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, 1994 (reprint, first published in 1895). Lincoln, Abraham. Abraham Lincoln: Selected Writings. New York: Barnes and Noble, 2013. Phillips, Donald T. Lincoln on Leadership for Today. Boston & New York: Houghton, Mifflin, Harcourt, 2017. Van De Linden, Frank. The Dark Intrigue: The True Story of a Civil War Conspiracy. Golden, CO: Fulcrum Publishing, 2007.

End Notes:

1. Lincoln, p. 6. The speech was to the Springfield Lyceum in 1838.

2. Churchill, pp. 279-80, 286, 316.

3. Chamberlain, p. 211.

4. Ibid.

5. Lamon, p. 275. Phillips, p. 252.

6. Chamberlain, p. 212.

7. Holzer, p. 309. (The address by Mr. Douglass occurred at the Cooper Union Building after Lincoln’s death. The speech is found at the Library of Congress.) Lamon, p. 261. Van Der Linden, p. 185.

8. Van Der Linden, p. 247.

9. Lamon, pp. 270, 273.

10. Brooks, p. 231.

11. Ibid., p. 236.

12. Lincoln, p 727 (Lincoln’s 2nd Inaugural Speech)

13. Lincoln, p. 731.

14. Ibid., p. 709.

15. Goodwin, p. 748.

16. Brooks, p. 228.