Brigadier General Hobart Ward: Nine Times Wounded

by Diana Loski

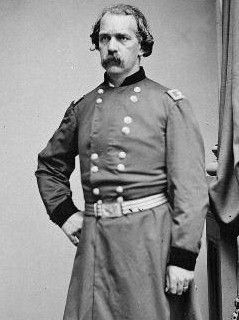

Brig. Gen. J.H.H. Ward

(National Archives)

Because the Peach Orchard and the Emmitsburg Road were about a half mile from the main Union line on Cemetery Ridge and the Round Tops, Sickles knew he needed to put some of his troops closer to that line – especially since he was blatantly disobeying orders from General Meade. He placed a brigade in the Wheatfield, and another in Devil’s Den. Large gaps yawned between the positions – an action that led to desperate consequences. The deployment proved especially disastrous for the brigade led by a forty-year-old veteran soldier, Brigadier General Hobart Ward.

Hobart Ward is one of those rarely remembered for his service. He was wounded nine times performing his duties in two wars. He was born John Henry Hobart Ward on June 17, 1823 in New York City to James and Esther Ward. He was named in part for his grandfather, John, who served in the American Revolution. Both his father and his grandfather were crippled by wounds in their respective conflicts. Although they survived their wars, they both died early due to the severity of their disfiguring wounds.1

Hobart (he was known by his cognomen, or second middle name) graduated from Trinity College, and at age eighteen decided to follow in the footsteps of his father and grandfather by joining the military. He fought in the War with Mexico. He received his first wound at the Battle of Monterrey, where he was commended for gallantry by General Winfield Scott. After the war, Scott recommended Ward to the post of assistant commissary-general of the army. He wrote that Ward was “a good citizen, a good soldier, and a gentleman.” Another fortunate denouement occurred from Ward’s time in Mexico – he met a young woman in Vera Cruz, and at war’s end he married her.2

Ward served as the assistant commissary-general in New York City for four years, from 1851-1855. He was then promoted to the position of commissary-general, as the person in charge of supplying provisions for the Federal army. It was during this time that he and his wife, Isabella, raised their five children.3

When the clouds of war enveloped the nation, Hobart Ward, who was already serving in the state militia, raised a New York Regiment, the 38th New York Infantry. He became its first colonel. He led the 38th in their baptism of fire at Bull Run in the summer of 1861, where over a hundred of his men were killed or wounded. Colonel Ward continued to lead them in the battles of the Peninsula Campaign during the spring of 1862. They fought at Second Bull Run in the summer. In the fall of that year, he was promoted to the rank of brigadier general on the previous recommendation of his late corps commander, General Philip Kearny. Ward was then moved into the Army of the Potomac. He commanded the 2nd Brigade, of the 1st Division of the Federal Third Corps.4

Ward led his brigade at Fredericksburg and Chancellorsville, and was in command as the Third Corps made their way into Gettysburg. They arrived in the early hours of July 2, 1863. They finally deployed, ordered at noon by their division commander David Birney, into the Wheatfield and later into Devil’s Den. Captain Harvey Munsell of the 99th Pennsylvania, said in a letter home, “There stood the 99th as firm as the rocks beneath their feet; watching and waiting for the avalanche of maddened men bearing down upon them – a cyclone.”5

Ward commanded six regiments and two units of U.S. Sharpshooters, the latter under the command of Hiram Berdan. Ward's other regiments included the 20th Indiana, the 3rd and 4th Maine, the 86th New York, the 124th New York, and the 99th Pennsylvania. The 3rd Maine and the sharpshooters were sent to the skirmish line. The remaining five regiments formed a single line of defense among the rocks and attempted to stretch to the right toward the Wheatfield – commanded by Brigadier General Regis de Trobriand.

The line was already thin, considering the area they needed to defend. The brigade was also far from reinforcements, having vacated the main Union line.

When General Longstreet on the Confederate line saw the men in blue along the Emmitsburg Road and away from the Round Tops, he hurriedly sent in his troops to grasp the Union high ground. Soon Ward’s Brigade saw the numerous lines of men in gray and butternut rushing toward them.

A large field lay between Ward’s men and the oncoming Confederates, triangular in shape, bordered by Rose’s Woods and stone fences. This triangular field sloped downward, but it did not seem to deter the determined rebel fighters. Ward’s Brigade stood firmly, as they needed not just to defend their line, but also to protect four Parrott guns belonging to Captain Smith’s Union Battery, deployed at the top of Devil’s Den. The Confederates, who consisted of General Benning’s Georgia Brigade and General Robertson’s Texans and Arkansas men, outnumbered Ward’s men about three to one. The height, rocks, and large guns helped deter the Southern attackers, but not for long.

The men of the 124th New York, fairly new to battle, charged into the Triangular Field, momentarily stunning the Confederate advance. One combatant remembered that “the second line of the foe staggers and falls back; but another and solid line takes its place, whose fresh fire falls with frightful effect.” The 124th took heavy casualties. Their colonel and major were both killed. Colonel Wheeler of the 20th Indiana was also killed.6

At the same time, the fight for Little Round Top was about to begin. General Warren, a member of General Meade's staff, saw that no troops held Little Round Top. He quickly sent infantry to the heights – troops from the 5th Corps who were on their way to the Wheatfield and Devil’s Den to aid the beleaguered soldiers there.

Two Alabama regiments, the 44th and the 48th, part of the Alabama Brigade scaling the heights of Big Round Top, descended into the valley near Plum Run. Behind Ward’s men in Devil’s Den, the Alabamians began firing at them. These veteran troops were ordered to take Smith's artillery, and they were determined to succeed.

At this time, the firing became incessant. An officer of the 20th Indiana requested more ammunition, as they were running low. General Ward, who had requested reinforcements, had no ammunition to give. He said “to hold until out and then fall back.”7

One soldier remembered the Den was a maelstrom of “ oaring cannon, crashing rifles, bursting shells, hissing bullets, cheers, shouts, shrieks and groans.” It was at this chaotic time that General Ward was wounded, though not severely. He remained on the field, refusing to leave his men.8

War is a numbers game, and the volume of Confederates in Devil’s Den overwhelmed Ward’s Brigade as reinforcements came too late. Texans and Georgians stormed the den. Some attempted to scale Little Round Top, which swirled with a stormy battle of its own. At the end of the day, Devil’s Den and the Union battery there fell into Confederate hands. A portion of the Wheatfield also went to the men in gray. Little Round Top, however, remained in Union hands.

Dan Sickles, who had been severely wounded in the Peach Orchard, had heard of Ward’s stubborn resistance and wished to commend him for a promotion to Major General. “His services have been so conspicuous and brilliant,” Sickles wrote, “that he deserves this recognition of merit.” While Ward had shown great temerity, he was nevertheless overlooked for the brevet, as the Federal Third Corps had taken a terrible thrashing for Sickles’s move at Gettysburg. When reorganization occurred in the months after the battle, the remnants of the Third Corps were absorbed into other corps, mainly the Federal Second and Fifth corps. The survivors of Ward’s Brigade were transferred to the Second Corps.9

While the next official battle between Generals Meade and Lee did not occur until the spring of 1864, there were skirmishes and smaller conflicts during what was called the Mine Run Campaign during the fall of 1863. General Ward was wounded twice during that time.10

The year 1864 would prove fateful and unpleasant for General Ward. During the next major battle at The Wilderness in Virginia in May of that year, the general’s actions caught the attention of General Hancock, and not in a positive light. During the fight in dense woods, General Ward and his brigade captured a Confederate general. Ward began to lead him to the rear. He turned the general over to a guard and sat on a caisson to take him back to the front. A member of General Hancock’s staff witnessed Ward sitting on the caisson and bluntly asked him why he was not leading his troops. The officer urged Ward “to take command ” as the battle still raged. Ward did so, and claimed success in “repulsing the enemy”. The battle was considered inconclusive, as both sides could not feasibly claim victory. The new commander of the Union forces, General Grant, did not retreat, but doggedly followed General Lee and his army. General Hancock placed Ward under temporary arrest for what he termed “behaving badly in the face of the enemy ”.11

At Spotsylvania, a few miles away, the North and South clashed again in the ensuing days. General Ward and his brigade fought against the Confederate line in the Laurel Hill area, when a shell fragment wounded the general, dazing him. While they fought bravely and broke the rebel line, they were ultimately forced to withdraw. Soon afterward, the convalescing Ward heard the news that he was under arrest for intoxication.12

“It is with deep astonishment and regret I learn that my reputation as a soldier has been impugned,” Ward wrote to General Birney. “I appeal…to you and to every officer and soldier in this Division to vindicate my character.” He argued that he could not conceive “ how my motives could be so misconstrued.”13

General Birney made no move to assist Ward, and in July the general who fought so valiantly in Devil’s Den was dismissed from the army. Because of friends who knew his character, Ward received an honorary discharge. He also received an honorary sword from his brigade. His last war was over. The attack on his character as a soldier hurt him worse than all nine wounds together.14

Ward returned to Brooklyn to his wife and children. Already a member of the Masonic Lodge, Ward continued to attend meetings. He became the clerk of the Superior Court of New York in 1871, and served in that position for the rest of his life.

At the age of eighty, Ward sported “a long white mustache and broad shoulders…[he] frequently attracted the attention of spectators in the State Courts building.” When the courts adjourned for the summer, the general and his wife traveled to Orange County, New York. One of his daughters had preceded them in death, and they wanted to visit her grave.15

While walking near Monroe, New York, Hobart Ward crossed some railroad tracks and did not hear an approaching train. He was hit. He was carried from the tracks alive, but died soon afterward from shock and his injuries.16

Ward’s funeral was a crowded one, with dignitaries, Masons, and veterans in attendance in addition to his family. One of those who attended was Dan Sickles, Ward’s old Gettysburg commander. After the funeral at the Aurora Grata Cathedral in Brooklyn, Ward was buried in Orange County near his daughter.

General Ward gave his uniform, boots, spurs and other accoutrements to Gettysburg National Military Park. The old commander took special care of his uniform – the one he was proud to wear in defense of his country – and especially among the boulders at Gettysburg, where he endured one of the worst storms of his long life. For conspicuous bravery – and for those nine wounds – he is fondly remembered.

Sources: The 99 th Pennsylvania File, Gettysburg National Military Park (hereafter GNMP). Brigade Marker, Hobart Ward’s Brigade, GNMP. The Brooklyn Citizen, 25 July, 1903. Drake, Francis Samuel. Appleton’s Cyclopedia of American Biography . Vol. VI. New York: Private Publisher, 1889. The Evening World (NYC), 24 July, 1903. Letter, JHH Ward to Gen’l David Birney, 10 May 1864, Participant Accounts File, GNMP. “Papers Relative to Mustering out of Gen. J.H.H.Ward”, Hobart Ward Participants Accounts File, GNMP. Pfanz, Harry W. Gettysburg: The Second Day . Chapel Hill, NC: The University of North Carolina Press, 1987. The New York Sun, 26 July, 1903. J.H.H. Ward Family Tree, Ancestry.com . Warner, Ezra J. Generals in Blue: Lives of the Union Commanders . Baton Rouge, LA: Louisiana State University Press, 1964 (reprint 1992). Weygant, Charles H. History of the One Hundred Twenty-Fourth Regiment NYSV . Newburgh, NY: Journal Printing House, 1877. Historical newspapers accessed through newspapers.com .

End Notes:

1. The Sun, 26 July 1903. Warner, p. 537. Drake, p. 378.

2. The Sun, 26 July 1903. Warner, p. 537.

3. JHH Ward Family Tree, Ancestry.com.

4. Drake, p. 378. Pfanz, p. 127.

5. 99 th PA File, GNMP.

6. Weygant, p. 176.

7. Pfanz, p. 183.

8. Ibid., p 187. Ward Brigade Marker, GNMP.

9. The Sun, 26 July, 1903. Warner, p. 538.

10. Drake, p 378.

11. Papers Relative to Mustering Out, Ward File, GNMP.

12. Ibid.

13. Letter, Ward to Birney, 10 May, 1864, GNMP.

14. The Sun, 26 July 1903. Birney died in the fall of 1864, and although Ward requested a hearing to exonerate himself, the death of Birney rendered it impossible.

15. The Evening World, 24 July, 1903. Warner, p. 538.

16. The Brooklyn Citizen, 25 July, 1903.