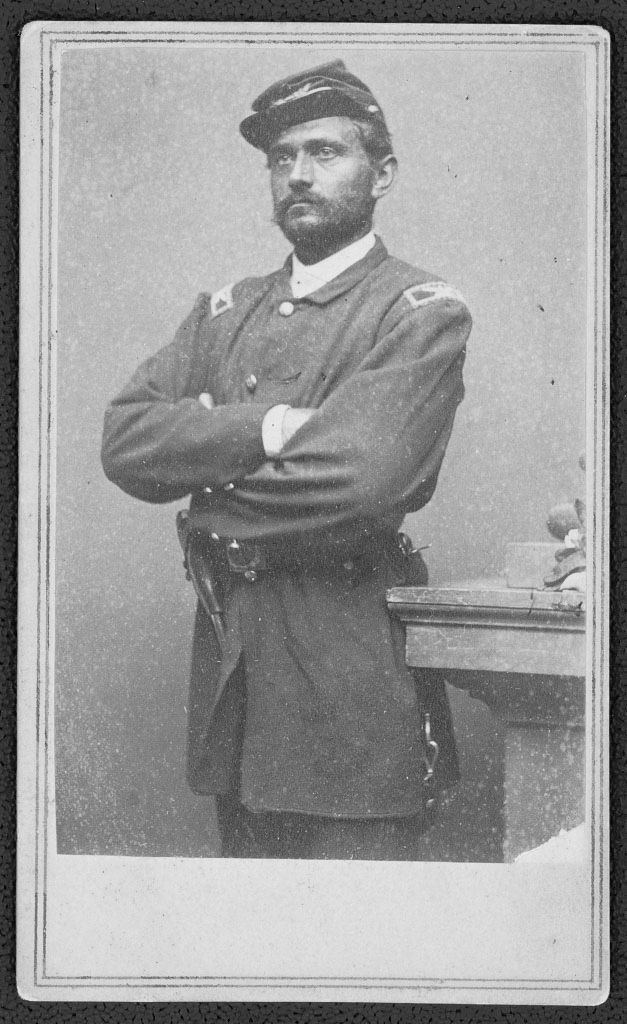

Colonel A.V. Ellis

(Library of Congress)

July 2, 1863 was a sweltering day, and the sun “had an angry look” as the men of the 124th New York Infantry deployed among the boulders of Devil’s Den. Unable to build breastworks due to the lack of earth around the monolithic rocks, they heard the roar of artillery from the ridge to their south. Soon a brigade of Texans swarmed across the Triangular Field, shouting the Rebel yell. The men in blue stood resolute, following their commander’s stoic stance. He was a soldier who exhibited a rare and exalted manhood.” He was Colonel Augustus Van Horne Ellis, and he was not about to retreat under any circumstance. 1

Augustus Van Horne Ellis was born on May 1, 1827 in Manhattan. He was the oldest of five sons born to Samuel and Eliza Ellis, and was named for his maternal grandfather, Augustus Van Horne. Like most born in the 19th century, Ellis was known by his middle name, Van Horne, and was called Van by close friends and family. His forebears were among the first Dutch settlers of Manhattan on his mother’s side. His paternal grandfather was an officer in the Continental army during the American Revolution.2

Ellis was both cerebral and athletic. He excelled in all subjects at public school and was a student at Columbia University in New York City. He earned high grades at college and had planned to study law, but did not graduate. He preferred instead a more adventurous outdoor life. He traveled to San Francisco as a young man and embarked upon shipbuilding and exploration. As a supervisor, he led a fleet of seven ships, journeying up the Pacific coast to the Columbia River, where he procured lumber for building materials. The merchandise acquired helped to build towns in California – a necessity with the ensuing Gold Rush. He became a member of the First California Guard, and earned money to purchase a yacht. With the new vessell, he sailed up the California coast for mining exploration. He collected various plants, ore, and a variety of shells during this expedition.3

With a continued interest in adventure, Ellis led an expedition to the Hawaiian Islands, and worked toward possible territorial annexation. He became a close friend and ally of the aging King Kamehameha, and purchased a homestead on the Big Island. When the Hawaiian king died, and annexation became unfavorable to the new ruler, Ellis remained on friendly terms with the new monarch. The new king requested that Ellis aid him in building a navy, so Ellis returned to New York in the attempt. The idea failed back on the mainland, since no territorial acquisition was forthcoming. Ever the entrepreneur, Ellis decided to purchase a steamer and made several mercantile voyages to Mexico.4

In 1857, Van Horne Ellis married Julia Verplank, and the couple settled in Windsor, Orange County, New York. War came during their fourth year of marriage, and Ellis immediately signed up to fight for the Union. He and his four brothers enlisted in the 71st Regiment, New York State Militia. They saw action at the Battle of First Manassas, where Ellis’s younger brother Julius was killed.5

In the summer of 1862, Abraham Lincoln issued a call for more Union soldiers. On the same day as the issuance, a committee met in Newburgh, New York to raise a new regiment from the citizens of Orange and Sullivan Counties. They unanimously selected Augustus Van Horne Ellis as the new commander.6

Captain Ellis was in Washington, D.C., serving with the 71st New York State Militia, when he received the proffered position. He accepted without hesitation, resigning his old commission within the hour. Ellis traveled to New York to recruit men for the new regiment, the 124th New York Infantry. And he was very selective. “A regiment of men is one thing ” Ellis said. “A regiment of fighting men is another thing.” Ellis wanted fighting men. The committee agreed: “ We…could not have chosen a better man – a braver or more efficient officer…than Colonel A. Van Horne Ellis,” one of the members said to the local newspaper.7

By August 8, 1862, only eight men had volunteered for the new regiment. Ellis worked tirelessly to find the needed numbers, and got them. Three weeks later the 124th New York was officially mustered. They left the depot at Newburgh on September 6 amid “ cheers loud and prolonged. At every depot crowds with loyal hearts sent after us shouts of approbation.”8

By the time they reached the front, the 124th New York had missed the Battle of Antietam. They were present, however, at the Battle of Fredericksburg on December 11, 1862. Held in reserve, they did not actively fight on the slopes of Marye’s Heights. Instead, their first battle as a unit was the Battle of Chancellorsville, as part of Sickles’s Federal Third Corps. Already, from their date of muster, the 124th New York had seen several commanders come and go from the Army of the Potomac. General George McClellan was their commander upon arrival, General Burnside commanded the army briefly at Fredericksburg and beyond during the terrible Mud March, and at Chancellorsville General Hooker was in command.

The Battle of Chancellorsville, in a wilderness area near Fredericksburg, was as disastrous as the preceding conflict had been. The Federal Third Corps deployed in the dense forest, in the middle of Lee’s two Confederate corps. Indecisive, Hooker delayed, a tactic that did not sit well with Van Horne Ellis. Ordered to support troops in the woods, the 124th New York found no troops to support. Told to wait for an aide to conduct them to their battle station, Ellis chafed under the lack of leadership from his superiors. He ordered a charge, and his men “rushed through the dwarf pines down the slope” to where the rest of the division stood. The division was then ordered back – a demand from Hooker – and disaster resulted as the two Confederate corps were now able to combine, delivering a blistering havoc to the Union troops.9

Lee’s trusted lieutenant-general, Thomas J. Jackson, eager to rout the Union forces, marched his troops through the woods to the Federal right flank – where the Union Eleventh Corps, thinking the fight had finished for the day, was encamped. Jackson’s men hurled themselves at the hapless troops, routing them in the twilight. In order to stop the Confederate advance, the Federal Third Corps, including the 124th New York, was ordered to make a stand. The men in blue, supported by artillery, stood firm, finally stopping the Confederates’ advance. In the interim, General Jackson was mortally wounded, likely by his own men, who failed to recognize their commander in the coming darkness.10

In his official report, Colonel Ellis wrote, “Our men fought like tigers, cheering loudly but falling fast. The officers without exception standing up to their duty.” He gave his men a nickname of endearment that was published in the local newspaper: The Orange Blossoms.11

They had fought well, and were now prepared for more of the same. They would get it at their next battle; they would have a new army commander as well. General George G. Meade took command of the Union army three days before the Battle of Gettysburg.

The Third Corps marched into Pennsylvania from Emmitsburg, Maryland, hearing the sounds of the first day’s battle but not arriving in time to fight that day. They reached Gettysburg after dark, having nearly missed running into Confederate troops near the Black Horse Tavern. Sickles was ordered to deploy to the left of the Federal Second Corps, but he liberally interpreted those orders. Sickles, a general due largely to his political prowess instead of military talent, had been a close friend to the recently removed General Hooker. Sickles disliked Meade, and he disliked the seeming lack of prudent judgment of the Union high command. Seeing ground that he thought was an improvement, Sickles moved his corps away from Cemetery Ridge and the Round Tops, where the rest of the Union troops were supposed to be deployed, toward the Emmitsburg Road. He not only took his ten thousand men out from the main line, he split them up, placing Hobart Ward’s Brigade in Devil’s Den, Regis de Trobriand’s Brigade in the Wheatfield, and the large remainder along the Emmitsburg Road in Sherfy’s Peach Orchard. The 124th New York, part of Ward’s Brigade, found themselves among the elephantine boulders of Devil’s Den. Large gaps yawned between the troops.

While Ward’s Brigade has been criticized for not digging breastworks, the ground around the Den had little spare earth for sizable protection. Moreover, their commander, Sickles, was not a military man, he was a politician – and the fact that he deliberately disobeyed his commanding officer offers the best evidence of Sickles’s lack of martial experience. The act sealed the fate of his troops.

When General Longstreet saw the broken Union line, he decided to attack immediately, before Sickles’s movement could be corrected. During the late afternoon of July 2, at about 5 p.m., he ordered his two divisions that had recently arrived to move toward Sickles’s men.12

Texans and Georgians from Hood’s Division were soon visible from the Confederate line. Confederate cannon pummeled the New Yorkers in Devil’s Den, but Colonel Ellis was determined to hold the position. Soon men in both butternut and gray uniforms were seen and heard heading toward Devil’s Den.

Major Cromwell from the 124th New York approached the resolute Ellis and asked if he could lead a charge. Ellis replied in the negative. The New Yorkers watched as the Confederates drew closer, yelling and firing as they came. Again, Cromwell approached Ellis for permission to charge, and again Ellis, arms folded, calmly told him to stay on the line. Behind the 124th, Smith’s 4th New York Battery fired upon the approaching rebels, who were drawing ever closer. Cromwell insisted, “The men must see us today.” The Colonel nodded a terse approval. Then, not wanting to miss the action, Ellis jumped upon his horse and held out his sword.13

The sudden charge of the 124th New York stunned the advancing Confederates, and for a time, they were stopped in their advance. “The onset of the Orange County’s sons becomes irresistible,” remembered one veteran, “and the second line of the foe wavers and falls back; but another and solid line takes its place, whose fresh fire falls with frightful effect.” The gunfire hit several men, including Major Cromwell, who was killed instantly.14

“My God! My God, men!” Ellis shouted. “Your Major’s down! Save him, save him!”15

The men obeyed, risking their lives to bring back the body of their major. As they turned to look through the smoke, they could see their colonel still astride his horse, waving his sword. “ Victory

!” he shouted above the din. He smiled. And then he pitched forward in the saddle.16

A miniéball had penetrated the Colonel’s forehead just above the visor of his kepi. A staff officer caught him, and with the help of others, carried him and the body of Major Cromwell to a flat rock behind their position on Houck’s Ridge. Ellis never regained consciousness and died within the hour, as the Confederate forces overtook Devil’s Den. One member of the 124th recalled that “the slope in front was strewn with our dead.” The losses for the 124th New York at Gettysburg numbered 28 dead, 58 wounded and 7 missing.17

Devil's Den

(Author photo)

Lieutenant Henry Ramsdell, who served on Ellis’s staff, was entrusted with returning the bodies of Colonel Ellis and Major Cromwell back to New York.18

“So fell the hero, who, in the words of his commanding General ‘was one of those chivalric spirits that we sometimes read of but seldom encounter.”19

Colonel Ellis was buried next to his brother, Julius, at St. Mark’s Cemetery in Manhattan. He was mourned by his wife, his parents, his surviving brothers, and his many friends, both civilian and military. “ The flags of Newburgh were hung at half-mast, minute guns were fired, bells were tolled, and the places of business were closed during the burial service.”20

Shortly before his death, Ellis confided to his adjutant, Lieutenant Ramsdell, that he would not survive Gettysburg. Yet, he persevered, and stood resolutely upon the crest of Devil’s Den, calmly awaiting the inevitable.21

On July 2, 1884, a portrait statue of the intrepid colonel was dedicated at the spot marking the middle of the 124th New York line at Devil’s Den. It was one of the earliest New York memorials at Gettysburg. Ellis looks over the Triangular Field ever after, just as he did on the afternoon of July 2, 1863. It is the only Gettysburg monument depicting a regimental commander.22

It seems fitting that Ellis, the fighting man, should receive that unique honor.

One who knew him well lamented, “Oh, that all were such as he!”23

Unfortunately, he perished at Gettysburg, and many like him did the same.

The 124th NY Memorial, with Col. Ellis standing

(Author photo)

Sources: Account of Henry P. Ramsdell, April 16, 1918, 124th NY File, Gettysburg National Military Park (hereafter GNMP). “The Death of Colonel Ellis”, unpublished fragment, 124th New York File, GNMP. Dr. Samuel Ellis Family Tree, Ancestry.com . Freeman, Douglas Southall. R.E. Lee . Vol. II. New York: MacMillan Publishing, 1962 (reprint, first published in 1934). Hawthorne, Frederick W. Gettysburg: Stories of Men and Monuments . Hanover, PA: Association of Licensed Battlefield Guides, 1988. Houston, John W. “A Short Sketch of the 124th New York Volunteers: Orange Blossoms” 1893. 124th New York File, GNMP. The Newburgh Weekly Telegrapher, 16 July, 1863. Letter, Bernard R. Crystal (of Columbia University) to Mr. Edward Clock, Apr. 11, 1985. Letter, Henry Hopewell to “Dear Mother”, July 5, 1863, 124th New York File, GNMP. Pfanz, Harry W. Gettysburg: The Second Day . Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 1987. Vinton, Reverend A.H., Rector of St. Mark’s Church, New York City. “Augustus Van Horne Ellis, Colonel 124th Regiment, New York Volunteers”. 124th New York File, GNMP. Weygant, Charles H. History of the One Hundred Twenty Fourth Regiment, NYSV . Newburgh, NY: Journal Printing House, 1877. Copy, GNMP.

End Notes:

1. Weygant, p. 174. Vinton, p. 4.

2. Dr. Samuel Ellis Family File, Ancestry.com .

3. Letter, Bernard Crystal to Mr. Edward Clock, Apr. 11, 1985.Vinton, p. 2.

4. Vinton, p. 2.

5. Ellis Family Tree, Ancestry.com.

6. Weygant, pp. 12-13.

7. Ibid., p. 14.

8. Ibid., p. 32.

9. Freeman, pp. 530-531. Weygant,p. 107.

10. Freeman, pp. 532-533. Weygant, p. 108.

11. Weygant, p. 130. Houston, “A Short Sketch”, 124th NY File, GNMP.

12. Pfanz, p. 150. Longstreet’s two divisions that were present were Hood’s and McLaws’s. Pickett’s Division was not yet at Gettysburg.

13. Pfanz, p. 187. Weygant, p. 175.

14. Weygant, p. 176.

15. Ibid.

16. Vinton, p. 4. Newburgh Weekly Telegrapher, 16 July, 1863.

17. Weygant, p. 179. “Death of Colonel Ellis”, 124th NY File, GNMP. Vinton, p. 4. Letter, Henry Ramsdell to “Dear Mother”, 5 Jul. 1863. Lt. Col. Francis Cummins took over the regiment at Col. Ellis’s death.

18. Account of Henry P. Ramsdell, April 16, 1918. 124th NY File, GNMP.

19. Vinton, p. 4. General Ward gave this tribute to Ellis.

20. Ibid.

21. Account of Henry P. Ramsdell,Apr. 16, 1918.

22. Hawthorne, Frederick W., p. 61.

23. Vinton, p. 5.