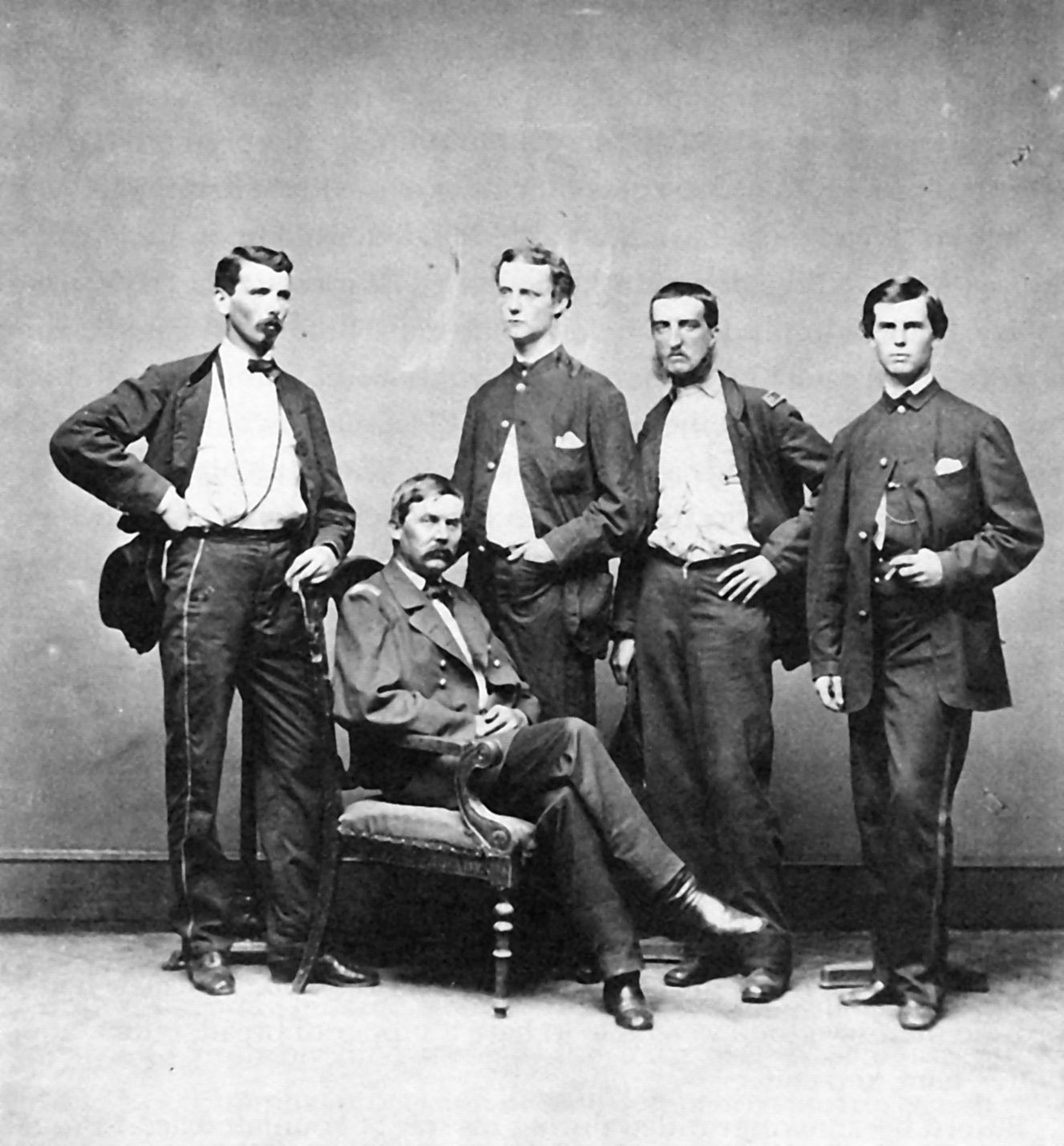

General Buford (seated) & staff, 1863.

Capt. Myles Keogh stands at far left

(Library of Congress)

On June 30, 1863, a lone general in blue sat on his horse near the town’s center, known then as the Diamond, deep in thought. John Buford contemplated what was about to transpire in the crossroads town of Gettysburg. Confederates were approaching from the west with the Union not far behind marching from the south, and he knew a battle was imminent. Alerting his staff, he sent word by them to ask permission to engage the encroaching men in gray the next morning.

One of those staff members was 23-year-old Myles Keogh, a young captain who was called by one superior as “one of the most gallant and efficient young cavalry officers I have ever seen.

” At Gettysburg and beyond he always did his duty, even after the close of the Civil War.1

Myles Walter Keogh (the surname is pronounced Key- Oh

, with the accent on the second syllable) was a native of Ireland. He was born in the town of Leighlinbridge in County Carlow, located about fifty miles south of Dublin. He was the third son of twelve children born to farmers John and Margaret Keogh. The family members were devoted Catholics, like most of those in 19th century Ireland. Although the family was not wealthy, they were prosperous by 19th century Irish standards. With his older brothers slated to inherit most of their father’s property, Myles, as the third son, decided to embark on a military career. A soldier’s life intrigued him, due in part to all the unrest in his nation and in part to defend his faith. He journeyed to Italy while still in his teens and joined forces to protect the pope during the Papal War of 1860. At the end of the conflict, he was awarded a medal for gallantry and a Cross of Knight of the Order of St. Gregory for his military prowess and personal bravery. He also wore around his neck a pendant with the words “Agnus Dei”, meaning Lamb of God,

a symbol of his faith.2

George A. Custer

(Library of Congress)

In Washington, William Henry Seward, Lincoln’s Secretary of State, was concerned with the depleting number of Union officers due to recent Civil War battles. He actively sought recruits to fill the ranks for the Army of the Potomac. He sent the Catholic Archbishop of New York to Europe to find as many as possible who were willing and able to fight for the Union cause. Myles Keogh was promised the rank of captain if he would come to the United States. In the spring of 1862, Captain Keogh was on a ship bound for a broken America.

Keogh first served on the staff of General James Shields, a colorful Irish commander from Illinois. Apparently, Myles was such an impressive officer that by the summer, he was transferred to the Army of the Potomac at the request of General George B. McClellan, on whose staff he then served.

Keogh was wounded in a cavalry battle that was at the time of Second Manassas in August. It was called the Lewis Ford engagement. Keogh was, however, recovered in time to participate in the Battle of Antietam in September. Although Antietam ended as a Union victory (albeit a dubious one), Lincoln removed the recalcitrant McClellan from command and replaced him with Ambrose Burnside. With McClellan out of the army, Keogh was placed on the staff of the man who would become like a second father to him, the intrepid cavalry commander John Buford.3

Buford’s troops participated in the Fredericksburg Campaign, but Buford expressed concerns about the aptitude of the new army commander. Burnside was not adept at utilizing cavalry, which rankled Buford and his men. Captain Keogh, a capable soldier, joined his leader in his concerns. The terrible Union losses at Fredericksburg confirmed their suspicions.4

With the coming of the year 1863, Lincoln replaced Burnside with Joe Hooker. Hooker at first appeared to be a capable leader. He raised both hopes and expectations as he made the Army of the Potomac a better fed and highly equipped unit. Hooker sent the commander of cavalry, General George Stoneman, on a raid in Virginia at the same time he planned to fight General Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia near a wilderness called Chancellorsville. On May 1, the outnumbered Confederate troops dealt a decisive blow to the unprepared Hooker, who blamed Stoneman’s absence for the loss.

An enraged Stoneman resigned his commission and went to command the capital troops in Washington D.C. He was replaced by political favorite Alfred Pleasonton. John Buford was promoted to division command, though he remained a brigadier general. Myles Keogh, retaining the rank of captain, continued to serve on Buford’s staff. All were equally displeased with Stoneman’s departure and Hooker’s inept leadership.5

Buford’s shining moment, which would be shared by his staff and troops, came with the Battle of Gettysburg.

The Union cavalry had, by 1863, risen in ability – due in part to leaders like Buford, and the perspicacity of political leaders like Seward, who procured able officers who could properly serve in the cavalry. When General Lee decided to invade the North, he and his army believed that the Federal forces would have no idea where they were. They were incorrect in their assumption: Buford and his cavalry tailed them easily as they wound their way through the Appalachian Mountains into Pennsylvania. The two cavalries clashed en route in mid-June at Brandy Station, Virginia – which should have alerted Lee to his coming predicament. The hours-long clash ended in a draw as both sides of cavalry retreated with hundreds dead and wounded, but the horsemen in blue had shown their mettle to the Confederates.

Buford and his staff joined two brigades of Buford’s Division in Gettysburg on June 30, 1863. Riding up Washington Street and on their way to the Lutheran Theological Seminary west of town, the men were greeted enthusiastically by young women. The civilians had also seen the Confederate troops – Jubal Early’s Division had invaded on June 26 – and they were ecstatic at the arrival of men in blue. “ They were Union soldiers and that was enough for me ,” remembered 15-year-old Tillie Pierce, “ for then I knew we had protection, and I felt they were our dearest friends. ” The troops were elated at the generous welcome. Just days before, another new army commander was placed at the head of the Union army. He was Major General George Meade.6

While John Buford deservedly has received praise for his astute protection of the high ground at Gettysburg, those who served with him had carried out his orders. Captain Keogh was one of the officers who relayed messages and returned to General Buford with essential information to Generals Meade and Reynolds that was needed to carry out the cavalry’s determined defense west of town.

A Vatican Guard. Myles Keogh wore a similar uniform.

(Photo courtesy of Stephanie Hedman)

Captain Keogh and Buford’s three other staff officers worked furiously during the first day’s battle at Gettysburg against a decidedly larger Confederate contingent. Buford’s two brigades under Colonels Gamble and Devin held their positions firmly until the arrival of the Union’s First Corps, who were 10,000 strong under the intrepid General John Reynolds. With the number of combatants more evenly matched, the infantry took over the fight. For the remainder of the battle, Buford’s troops were deployed to guard the flanks of the army, protect telegraph stations, and to continue scouting. After the battle, they did their work to assess the enemy position during the Confederate retreat into Virginia.7

Myles Keogh was promoted to the rank of major after Gettysburg for “gallant and meritorious services.”8

The next several months were equally exhausting and troublesome for Buford’s cavalry. Riding, scouting, and relaying information pertaining to the whereabouts of Lee’s men resulted in almost no action, with the exception of minor clashes at Bristoe Station. General Meade, already fighting for his honor in Washington due to salacious lies told by General Dan Sickles and his political allies, was not eager to bring on yet another colossal confrontation. Due to the heavy losses at Gettysburg, active recruitment was ongoing. Myles Keogh took some needed leave to visit friends in New York.9

By late autumn, Buford grew seriously ill. George Stoneman took him to his own home in Washington to ensure better care. When Major Keogh learned of his commander’s dangerous situation, he rushed to Washington. By mid-December, it was clear that Buford – ill with a combination of typhoid fever and pneumonia – was dying. He was too worn out to fight either disease, each decidedly deadly enough by themselves. As infected water filled his lungs, a delirious Buford found breathing difficult. Major Keogh climbed onto the bed and lifted his commander to a sitting position to ease his breathing. It was there on Wednesday, December 16 that Buford died, in Keogh’s arms. Stoneman and the rest of Buford’s staff were present. All were devastated at the tremendous loss.10

Keogh was a pall bearer at Buford’s funeral on December 20. He was also, along with the rest of Buford’s staff and many of his troops, undertaking raising funds for the beloved commander’s tombstone at West Point.

Keogh was then sent to General William Tecumseh Sherman, who, in 1864, was given command of all Union troops in the western theater of the war. Keogh served on Sherman’s staff for that year, including at the decisive Battle of Atlanta. Learning of the plight of many unfortunate Union soldiers at Andersonville Prison in southwestern Georgia, Sherman sent General Stoneman and Keogh (and a contingent of capable cavalry soldiers) to Andersonville in an attempt to free the hordes of starving and dying prisoners of war. The attempt failed and the men were captured on July 31. Fortunately for Stoneman and Keogh, officers were sent to Libby Prison instead of Andersonville. After two months as prisoners, Sherman negotiated their release.11

Stoneman, who knew Keogh well, said, “Major Keogh is one of the most superior young officers in the army and is a universal favorite with all who know him.”12

With Grant at the head of the Army of the Potomac in the eastern theater, and Sherman in charge of the western theater, the attrition of the Confederate armies increased. With Lincoln’s reelection in November 1864, the end of the war was in sight. Major Keogh was not at Appomattox Court House to witness Lee’s surrender on April 9, 1865. He was instead at the surrender of Joe Johnston to General Sherman near Bentonville, North Carolina, two weeks later. The formal surrender of General Johnston’s army, on April 26, numbered close to 25,000 men; it was the second largest surrender of the war, after General Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia.

After the end of the war, as most of the volunteer soldiers and generals returned to their families, Myles Keogh, a bachelor, decided to reenlist in the post-war army. With fewer soldiers needed, generals became colonels and many officers lost their ranks. Keogh served in the 7th Cavalry with the rank of lieutenant, but soon regained the rank of captain. The 1870 census finds him living in Riley, Kansas, stationed at Fort Leavenworth.13

With many Civil War veterans going west after the war, the American frontier held its own uprising issues. The Federal government forced the native populations to relocate to reservations. Many tribes acquiesced, but others were hostile to this new law and refused. Attacks on civilians inhabiting the sparsely populated central plains increased. The 7th Cavalry, led by Gettysburg veteran commander John Gibbon – who ended the war a Major General of infantry and was now a colonel of cavalry – was ordered to head west as part of a larger force to ensure that the tribesmen abandon their villages and inhabit the reservations. Gibbon’s second in command was Lt. Colonel George Armstrong Custer, who had been, at age 23, the youngest general at the Battle of Gettysburg. He had commanded a brigade in Gregg’s Cavalry Division at Gettysburg, while Keogh had served with Buford.

During a foray into Dakota Territory, one of the men from Keogh’s company found a young horse in a ravine, injured and weakened by lack of care. Keogh took the horse, which had run wild, and tamed it. The mixed breed horse, sleek and muscular with a long tail, resembled an auburn-brown bay. Keogh named the horse Comanche after the tribesmen of the plains who were renowned for their fighting spirit. The stallion and the captain were soon inseparable.14

In the summer of 1874, while Custer took some of the 7th Cavalry into Dakota Territory looking for tribes to capture, Myles Keogh returned to Ireland to see his family. His parents had passed away during the Civil War, and his brothers, who prospered, had families of their own. He spent time with his younger sisters, most of them unmarried. Myles had inherited an estate, which he transferred to his sister, Margaret, so that she and his other sisters would have a living. He stayed in Ireland for seven months. Upon his return to the United States in 1875, he changed his will and took out a life insurance policy.

15

In 1876, Captain Keogh was in charge of two companies in the 7th Cavalry. Before leaving for Montana Territory, he penned a letter, with which he attached a copy of his will, to a family in Auburn, New York, whom he considered his closest friends.

“We leave Monday on an Indian expedition and if I ever return, I will go on and see you all. I have requested to be packed up and shipped to Auburn in case I am killed, and I desire to be buried there. God bless you all, remember if I should die – you may believe that I loved you and every member of your family – it was a second home to me.”16

The Little Bighorn River in south central Montana is situated just north of the Wyoming border. It meanders through a vast and arid valley surrounded by bluffs and ravines. Even today it gives off a nether-worldly atmosphere, where rattlesnakes and antelope seem to be the only inhabitants. The 7th Cavalry had a difficult time there finding the hidden villages of the varied tribes that consisted of mostly Sioux and Cheyenne. The Native Americans consistently moved and hid themselves when the government troops invaded the area, and Custer was increasingly frustrated that his prey continued to elude him. The troops were also low on supplies, waiting for the next boat of provisions to dock upriver.

Lt. Colonel Custer decided on a bold plan to split his portion of the troops, with the intent to find the tribes and attack them. He sent a separate detachment under Major Marcus Reno to draw out the warriors, while he and his troops scouted additional areas. Captain Keogh commanded two companies who searched ravines and bluffs in the vicinity. It appears that Custer acted on his own volition, without Gibbon’s approval. In all, there were less than 300 in Custer’s command on June 25, 1876. Custer ordered Keogh and his men to serve as the rear guard.17

The result of Custer’s rash decision, combined with the vast territory and underestimation of the tribal numbers, resulted in the Battle of Little Bighorn, which took place on June 25, 1876. Approximately two thousand warriors, led by many chieftains, including the renowned Crazy Horse and Sitting Bull, attacked Custer's small and divided force. They thrust themselves easily upon Major Reno, who quickly retreated and managed to survive with half his troops left on the field. The tribes then attacked Custer’s men, who were widely scattered in the Little Bighorn Valley. Myles Keogh and his men were among the first to fall. Captain Keogh was shot twice, in the knee and the chest. The 36-year-old was killed instantly.18

Custer made it to a small hill near the center of the valley, where, surrounded by the survivors of his men, he too was shot. None of Custer’s squadrons survived. The fight lasted slightly longer than Pickett’s Charge at Gettysburg: about an hour and fifteen minutes.19

On June 28 members of the 7th Cavalry found the stripped, dismembered and mutilated bodies of Custer’s men. Only a few had been left intact. One was Custer. Another was Myles Keogh. He still wore his Agnus Dei necklace. The warriors, who must have recognized it as a religious symbol, had left him in peace.20

Captain Keogh was buried near the spot where he fell. A year later, his remains were transferred to Fort Hill Cemetery, a national cemetery, in Auburn, New York – as he had requested. He was interred with full military honors.21

Comanche survived the Little Bighorn battle and, due to his popularity with the 7th Cavalry and out of respect for his owner, the horse was treated for his wounds and spent the remainder of his days as the mascot for the regiment.22

Like many soldiers, Captain Keogh apparently felt the premonition of death upon his return from his last visit to Ireland. Like many who served in the Civil War and later on the western frontier, he did not marry or have posterity to help preserve his memory. He is remembered for his devotion to duty, his universal affability and his affection for the nation he adopted as his own – and for which he gave his all to preserve.

Sources: Alleman, Tillie Pierce. At Gettysburg: Or What a Girl Saw and Heard of the Battle . Baltimore, MD: Butternut & Blue, 1994 (Reprint, first published in 1889). The Bismarck Tribune, 10 May 1896. Found in newspapers.com . Custer, Elizabeth B. Boots and Saddles . Santa Barbara, CA: The Narrative Press, 2001 (Reprint, first published in 1896). Keogh Family Tree, Ancestry.com . Myles Keogh US Military Records, National Archives, Washington, D.C. Longacre, Edward. General John Buford: A Military Biography . Pennsylvania: Combined Publishing, 1995. McGinley, John Joe. “Myles Walter Keogh: The Irish Hero of the US Civil War Who Died with General Custer.” IrishCentral.com . Pfanz, Harry W. Gettysburg: The First Day . Chapel Hill & London: The University of North Carolina Press, 2001. Phipps, Michael and John S. Peterson. The Devil’s To Pay: General John Buford, USA . Gettysburg, PA: Farnsworth House Military Impressions, 1995. Snelson, Bob. Death of a Myth: Seventh Cavalry at the Little Bighorn . Snelsonbooks.com, 2002. Warner, Ezra J. Generals in Blue: Lives of the Union Commanders . Baton Rouge and London: Louisiana State University Press, 1996 (Reprint, first published in 1964). Wells, Keith, ed. US Civil War Records and Profiles; Regulars of the US Army, 1789-1903 . Located at Ancestry.com . US Census Records, Riley, Kansas 1870. US National Cemetery Interment Form, 1909; found in Ancestry.com . Additional information on the Little Bighorn National Battlefield was found by the author during a visit there.

End Notes:

1. Wells, ed., p. 1083.

2. Keogh Family Tree, Ancestry.com . McGinley, IrishCentral.com . Two of the Keogh children died in infancy.

3. Longacre, p. 107.

4. Ibid., pp. 121-122.

5. Warner, p. 483.

6. Alleman, p. 28.

7. Pfanz, pp. 37-38.

8. McGinley, IrishCentral.com .

9. Warner, p. 316. Keogh US Military Records, NA.

10. Longacre, p. 245. Phipps, p. 62.

11. Warner, p. 443. Wells, p. 1084.

12. Wells, p. 1084.

13. US Census, 1870.

14. The Bismarck Tribune, 10 May, 1896.

15. McGinley, IrishCentral.com .

16. Wells, p. 1085.

17. Snelson, pp. 82, 87. Post-war regiments were back at full strength. Where a typical regiment had about 300-400 men in the ranks at Gettysburg, by the 1870s, a regiment was one thousand men. At Little Bighorn Custer had split his companies in an attempt to draw out the warring tribes.

18. Ibid., p. 83. The Sioux and Cheyenne warriors were amply armed with rifles. They also utilized tomahawks and arrows in the battle.

19. Custer, p. 231. Additional information provided by Little Bighorn National Monument.

20. Wells, p. 1084.

21. US Nat’l Cemetery Interment, 1909.

22. The Bismarck Times, 10 May, 1896.

Editor's Note: According to The Bismarck Times, Comanche lived to the ripe old age of 30 or possibly older. He passed away in 1896. According to the article, he was discovered in 1867.

Captain Keogh and Buford’s three other staff officers worked furiously during the first day’s battle at Gettysburg against a decidedly larger Confederate contingent. Buford’s two brigades under Colonels Gamble and Devin held their positions firmly until the arrival of the Union’s First Corps, who were 10,000 strong under the intrepid General John Reynolds. With the number of combatants more evenly matched, the infantry took over the fight. For the remainder of the battle, Buford’s troops were deployed to guard the flanks of the army, protect telegraph stations, and to continue scouting. After the battle, they did their work to assess the enemy position during the Confederate retreat into Virginia. 7

Myles Keogh was promoted to the rank of major after Gettysburg for “ gallant and meritorious services.”

8

The next several months were equally exhausting and troublesome for Buford’s cavalry. Riding, scouting, and relaying information pertaining to the whereabouts of Lee’s men resulted in almost no action, with the exception of minor clashes at Bristoe Station. General Meade, already fighting for his honor in Washington due to salacious lies told by General Dan Sickles and his political allies, was not eager to bring on yet another colossal confrontation. Due to the heavy losses at Gettysburg, active recruitment was ongoing. Myles Keogh took some needed leave to visit friends in New York. 9

By late autumn, Buford grew seriously ill. George Stoneman took him to his own home in Washington to ensure better care. When Major Keogh learned of his commander’s dangerous situation, he rushed to Washington. By mid-December, it was clear that Buford – ill with a combination of typhoid fever and pneumonia – was dying. He was too worn out to fight either disease, each decidedly deadly enough by themselves. As infected water filled his lungs, a delirious Buford found breathing difficult. Major Keogh climbed onto the bed and lifted his commander to a sitting position to ease his breathing. It was there on Wednesday, December 16 that Buford died, in Keogh’s arms. Stoneman and the rest of Buford’s staff were present. All were devastated at the tremendous loss. 10

Keogh was a pall bearer at Buford’s funeral on December 20. He was also, along with the rest of Buford’s staff and many of his troops, undertaking raising funds for the beloved commander’s tombstone at West Point.

Keogh was then sent to General William Tecumseh Sherman, who, in 1864, was given command of all Union troops in the western theater of the war. Keogh served on Sherman’s staff for that year, including at the decisive Battle of Atlanta. Learning of the plight of many unfortunate Union soldiers at Andersonville Prison in southwestern Georgia, Sherman sent General Stoneman and Keogh (and a contingent of capable cavalry soldiers) to Andersonville in an attempt to free the hordes of starving and dying prisoners of war. The attempt failed and the men were captured on July 31. Fortunately for Stoneman and Keogh, officers were sent to Libby Prison instead of Andersonville. After two months as prisoners, Sherman negotiated their release. 11

Stoneman, who knew Keogh well, said, “Major Keogh is one of the most superior young officers in the army and is a universal favorite with all who know him.” 12

With Grant at the head of the Army of the Potomac in the eastern theater, and Sherman in charge of the western theater, the attrition of the Confederate armies increased. With Lincoln’s reelection in November 1864, the end of the war was in sight. Major Keogh was not at Appomattox Court House to witness Lee’s surrender on April 9, 1865. He was instead at the surrender of Joe Johnston to General Sherman near Bentonville, North Carolina, two weeks later. The formal surrender of General Johnston’s army, on April 26, numbered close to 25,000 men; it was the second largest surrender of the war, after General Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia.

After the end of the war, as most of the volunteer soldiers and generals returned to their families, Myles Keogh, a bachelor, decided to reenlist in the post-war army. With fewer soldiers needed, generals became colonels and many officers lost their ranks. Keogh served in the 7th Cavalry with the rank of lieutenant, but soon regained the rank of captain. The 1870 census finds him living in Riley, Kansas, stationed at Fort Leavenworth. 13

With many Civil War veterans going west after the war, the American frontier held its own uprising issues. The Federal government forced the native populations to relocate to reservations. Many tribes acquiesced, but others were hostile to this new law and refused. Attacks on civilians inhabiting the sparsely populated central plains increased. The 7th Cavalry, led by Gettysburg veteran commander John Gibbon – who ended the war a Major General of infantry and was now a colonel of cavalry – was ordered to head west as part of a larger force to ensure that the tribesmen abandon their villages and inhabit the reservations. Gibbon’s second in command was Lt. Colonel George Armstrong Custer, who had been, at age 23, the youngest general at the Battle of Gettysburg. He had commanded a brigade in Gregg’s Cavalry Division at Gettysburg, while Keogh had served with Buford.

During a foray into Dakota Territory, one of the men from Keogh’s company found a young horse in a ravine, injured and weakened by lack of care. Keogh took the horse, which had run wild, and tamed it. The mixed breed horse, sleek and muscular with a long tail, resembled an auburn-brown bay. Keogh named the horse Comanche

after the tribesmen of the plains who were renowned for their fighting spirit. The stallion and the captain were soon inseparable. 14