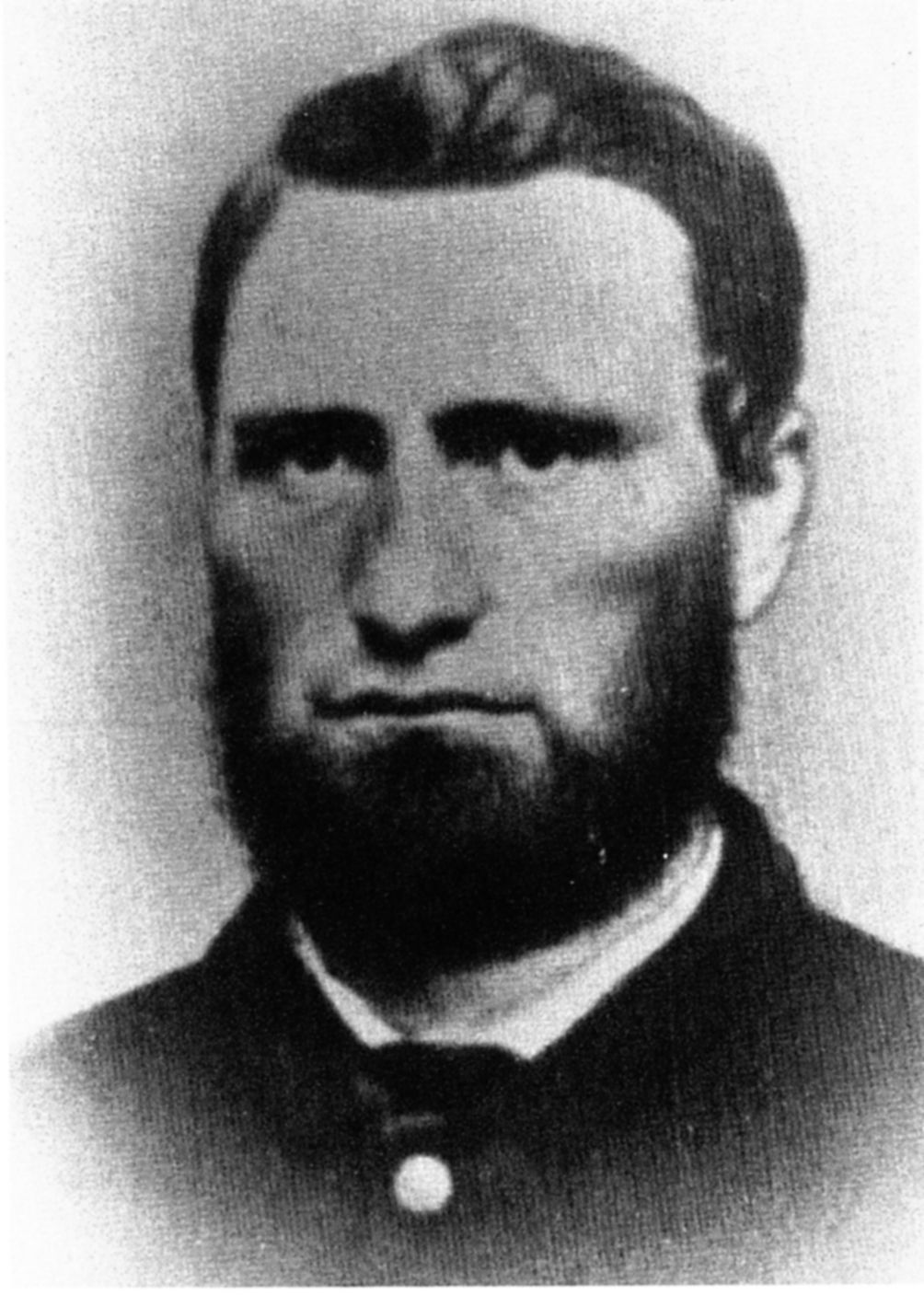

Sgt. Amos Humiston

(National Park Service)

Gettysburg, Pennsylvania was one of the first towns in America to commemorate the holiday originally known as Decoration Day. By offering a special annual recognition of those who were slain in the recent Civil War, this commemoration, now known as Memorial Day, began in Gettysburg in 1868.

The Soldiers National Cemetery in Gettysburg is the place where, each year, those who perished in the fight for liberty are still remembered by the traditional strewing of flowers by children on the graves of those who died at Gettysburg in 1863. The tradition began with the fate of one man, a husband and father, who died from a wound suffered during Gettysburg’s first day. His name was Amos Humiston.

Amos Humiston never set his sights on being a soldier. Born and raised in the village of Owego, New York, Amos was the youngest of four children. His father died far too soon, leaving his wife a widow with the children to raise. Times were difficult, and Amos was often loaned to work for the neighbors, a typical manner of raising funds in those days. By age 15, Amos left school and was apprenticed to a harness maker. In a few years, Amos, now a young man, tired of the trade and went to sea on a whaling ship. Within three years, he had traveled the South Pacific, the Arctic region and much of the Atlantic. He visited exotic places like the Sandwich Islands (present day Hawaii), and endured many dangers at sea, including multiple hurricanes. He had witnessed burials at sea – sending shipmates to watery graves – and found that, in spite of his many adventures, he accrued little in wages.

A much wiser Humiston returned to the village of Candor, near Owego, and decided to return to harness making. He joined his brother, a tanner, in business. Soon, he met a young widow, Philinda Smith, and the smitten former sailor soon courted her. They married on July 4, 1854. Three children were born to the couple: Franklin in 1855, Alice in 1857, and Frederick in 1859.

Amos moved his young family to the town of Portville, just north of the Pennsylvania border, where a thriving logging industry insured plenty of work for tanners and leatherworks, skills in which Amos Humiston excelled. When war erupted in 1861, the Humistons were well situated in their new hometown. Amos, thinking the war would be of short duration, and not wanting to leave his family, did not enlist at that time.

On July 4, 1862, Amos and Philinda celebrated their eighth anniversary together. The milestone was marred, however, with Abraham Lincoln’s call for additional soldiers. Amos felt that he could not ignore the summons, as many of his friends and relatives were answering the call. Philinda did not take the news well. She had already been widowed once, and feared she would lose her husband to the war. Amos stood by his decision. According to a close family friend, Philinda looked over her sleeping children on that July night and “sobbed in silence.”1

Amos enlisted in the 154th New York Infantry. The regiment left for war in late September 1862 with one thousand men in the ranks. The train bearing farmers and laborers, fathers and sons, left the nearby town of Olean for Elmira, New York and Baltimore, Maryland. They finally arrived in the Union capital of Washington. After a scant month of training, the 154th headed for Northern Virginia as part of the Federal Eleventh Corps, in the Army of the Potomac.

Upon their arrival, the men from New York realized that their corps comprised numerous nationalities – in fact, many of their fellow soldiers did not even speak English. Brigade and division commanders echoed the different ranks with names like Sigel, Schimmelfennig, von Steinwehr, and Krzyzanowski.

Because of the language barrier and the lack of New York men as commanders, the situation rankled the patriotic men of the 154th. To make matters worse, men from hamlets and villages like Humiston and his fellow compatriots were placed in the midst of men from the inner city, resulting in disease. Many of the men of the 154th fell ill with typhoid, smallpox, and influenza – and some died before ever seeing the front. In addition, the paymaster had overlooked the new recruits; the needed funds to send to their families were not issued. It was a problem that endured for several months.2

The Eleventh Corps missed the Battles of Antietam and Fredericksburg, due to the timing of their arrival and the subsequent illnesses. When Christmas passed that year, a homesick Amos wrote to his wife, lamenting the news of the continual Union losses. He penned, “ If I ever live to get home you will not complain of being lonesome again. Now kiss the children for me.” The winter months passed into the new year of 1863, and Humiston’s letters were filled with his love for his wife and children. “Take good care of the babies,” he admonished, “and kiss them for me.”3

In early 1863 General Joe Hooker replaced the affable but inefficient Ambrose Burnside as commander of the Army of the Potomac. Hooker immediately worked to improve the condition of his army. Soldiers began receiving their salaries, food and nutrition improved and sanitation replaced the former squalor. He also introduced corps symbols to increase unit pride. The Eleventh Corps was recognized by the crescent moon. General Sigel was replaced with Oliver Howard as the commander of the corps – which upset the many German soldiers but elated the New Yorkers. Amos Humiston rose in rank to a sergeant. Within a few weeks, the former seaman and harness maker would be tested in his new position as battle loomed in a wilderness known as Chancellorsville.4

The Battle of Chancellorsville was the first engagement for the 154th New York. The Eleventh Corps formed the right flank of the Army of the Potomac. As the day waned and the battle appeared to cease, the soldiers prepared their supper and settled down for the evening. As darkness loomed the corps was surprised by an attack on their flank from the intrepid General Thomas J. Jackson and his corps of 30,000. The sudden appearance of men in gray swarming over the camp alarmed the men in blue and they gave way. The rout caused a stigma and great shame for the Eleventh Corps. In spite of the terrible outcome for the Union that day, Amos Humiston was cheered by a letter. Philinda had written, and enclosed an ambrotype of their three children.5

The Soldiers National Cemetery in Gettysburg is the place where, each year, those who perished in the fight for liberty are still remembered by the traditional strewing of flowers by children on the graves of those who died at Gettysburg in 1863. The tradition began with the fate of one man, a husband and father, who died from a wound suffered during Gettysburg’s first day. His name was Amos Humiston.

Amos Humiston never set his sights on being a soldier. Born and raised in the village of Owego, New York, Amos was the youngest of four children. His father died far too soon, leaving his wife a widow with the children to raise. Times were difficult, and Amos was often loaned to work for the neighbors, a typical manner of raising funds in those days. By age 15, Amos left school and was apprenticed to a harness maker. In a few years, Amos, now a young man, tired of the trade and went to sea on a whaling ship. Within three years, he had traveled the South Pacific, the Arctic region and much of the Atlantic. He visited exotic places like the Sandwich Islands (present day Hawaii), and endured many dangers at sea, including multiple hurricanes. He had witnessed burials at sea – sending shipmates to watery graves – and found that, in spite of his many adventures, he accrued little in wages.

A much wiser Humiston returned to the village of Candor, near Owego, and decided to return to harness making. He joined his brother, a tanner, in business. Soon, he met a young widow, Philinda Smith, and the smitten former sailor soon courted her. They married on July 4, 1854. Three children were born to the couple: Franklin in 1855, Alice in 1857, and Frederick in 1859.

Amos moved his young family to the town of Portville, just north of the Pennsylvania border, where a thriving logging industry insured plenty of work for tanners and leatherworks, skills in which Amos Humiston excelled. When war erupted in 1861, the Humistons were well situated in their new hometown. Amos, thinking the war would be of short duration, and not wanting to leave his family, did not enlist at that time.

On July 4, 1862, Amos and Philinda celebrated their eighth anniversary together. The milestone was marred, however, with Abraham Lincoln’s call for additional soldiers. Amos felt that he could not ignore the summons, as many of his friends and relatives were answering the call. Philinda did not take the news well. She had already been widowed once, and feared she would lose her husband to the war. Amos stood by his decision. According to a close family friend, Philinda looked over her sleeping children on that July night and “sobbed in silence.”1

Amos enlisted in the 154th New York Infantry. The regiment left for war in late September 1862 with one thousand men in the ranks. The train bearing farmers and laborers, fathers and sons, left the nearby town of Olean for Elmira, New York and Baltimore, Maryland. They finally arrived in the Union capital of Washington. After a scant month of training, the 154th headed for Northern Virginia as part of the Federal Eleventh Corps, in the Army of the Potomac.

Upon their arrival, the men from New York realized that their corps comprised numerous nationalities – in fact, many of their fellow soldiers did not even speak English. Brigade and division commanders echoed the different ranks with names like Sigel, Schimmelfennig, von Steinwehr, and Krzyzanowski.

Because of the language barrier and the lack of New York men as commanders, the situation rankled the patriotic men of the 154th. To make matters worse, men from hamlets and villages like Humiston and his fellow compatriots were placed in the midst of men from the inner city, resulting in disease. Many of the men of the 154th fell ill with typhoid, smallpox, and influenza – and some died before ever seeing the front. In addition, the paymaster had overlooked the new recruits; the needed funds to send to their families were not issued. It was a problem that endured for several months.2

The Eleventh Corps missed the Battles of Antietam and Fredericksburg, due to the timing of their arrival and the subsequent illnesses. When Christmas passed that year, a homesick Amos wrote to his wife, lamenting the news of the continual Union losses. He penned, “ If I ever live to get home you will not complain of being lonesome again. Now kiss the children for me.” The winter months passed into the new year of 1863, and Humiston’s letters were filled with his love for his wife and children. “Take good care of the babies,” he admonished, “and kiss them for me.”3

In early 1863 General Joe Hooker replaced the affable but inefficient Ambrose Burnside as commander of the Army of the Potomac. Hooker immediately worked to improve the condition of his army. Soldiers began receiving their salaries, food and nutrition improved and sanitation replaced the former squalor. He also introduced corps symbols to increase unit pride. The Eleventh Corps was recognized by the crescent moon. General Sigel was replaced with Oliver Howard as the commander of the corps – which upset the many German soldiers but elated the New Yorkers. Amos Humiston rose in rank to a sergeant. Within a few weeks, the former seaman and harness maker would be tested in his new position as battle loomed in a wilderness known as Chancellorsville.4

The Battle of Chancellorsville was the first engagement for the 154th New York. The Eleventh Corps formed the right flank of the Army of the Potomac. As the day waned and the battle appeared to cease, the soldiers prepared their supper and settled down for the evening. As darkness loomed the corps was surprised by an attack on their flank from the intrepid General Thomas J. Jackson and his corps of 30,000. The sudden appearance of men in gray swarming over the camp alarmed the men in blue and they gave way. The rout caused a stigma and great shame for the Eleventh Corps. In spite of the terrible outcome for the Union that day, Amos Humiston was cheered by a letter. Philinda had written, and enclosed an ambrotype of their three children.5

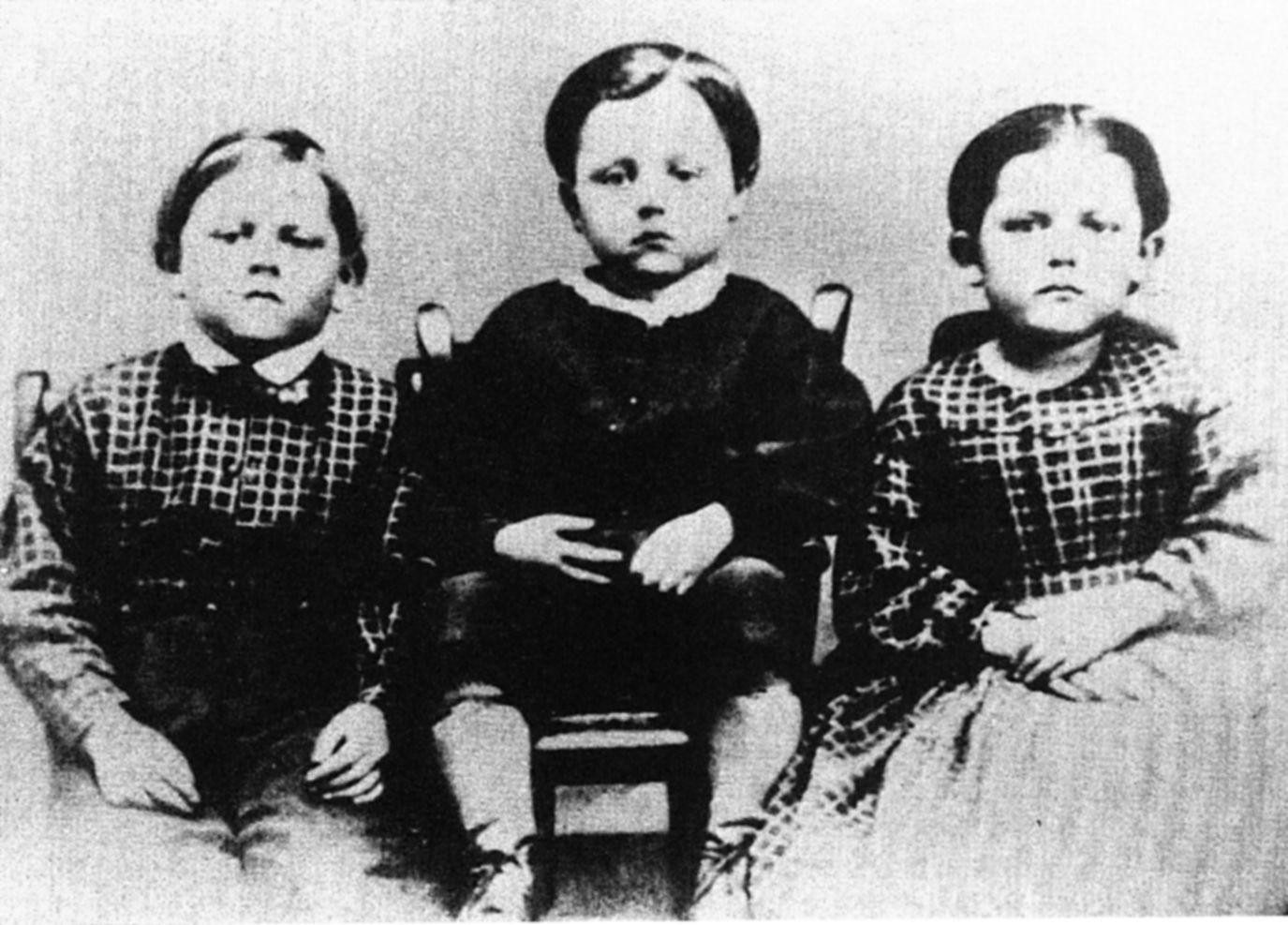

The photo of the Humiston children, found on their father at Gettysburg

(National Park Service)

Fate again played a hand with the overwhelming Confederate victory at Chancellorsville. General Robert E. Lee, inspired by the win, decided to take the war to the North. In spite of losing General Jackson during the flank attack on the Eleventh Corps, Lee was determined to end the war once and for all. He began his trek northward, splitting his two corps into three, arriving in Pennsylvania near the end of June. In the interim, Abraham Lincoln replaced General Hooker with General George Meade. The men in blue and gray collided west of the town of Gettysburg, Pennsylvania on the morning of July 1, 1863.6

The 154th New York, part of Colonel Charles Coster’s Brigade, were first deployed in the Evergreen Cemetery on Cemetery Hill south of town. The high command had noticed the hill and decided it was a good defensive position; however, the fight was still a few miles away to the west and, soon enough, included the north of town. As the battle worsened, and General Meade had not yet arrived, General Howard learned of the death of General Reynolds – the ranking commander on the field. Howard decided that “ the mighty panorama of war ” needed additional men at the front and sent Coster’s Brigade into battle. As the 154th rushed toward the fight, they saw their fellow soldiers already rushing back toward Cemetery Hill. The sight reminded them of Chancellorsville. Coster’s Brigade came too late to bolster the outnumbered Union troops, including men from their own corps.7

Had the 154th been at the front lines that day at Gettysburg, they might have had a chance to survive it. Instead, they were sacrificed for the sake of others’ survival. Near the railroad tracks in town, near Kuhn’s brickyard, the 154th made a valiant stand against a numerically superior enemy. Men from North Carolina and Louisiana crushed the battle line of the 154th New York. Lieutenant Colonel Allen, commander of the regiment, later recorded, “We were scarcely in position when the enemy, who were advancing in vastly superior numbers in our front, commenced the attack…We held the enemy in check…but their line of battle, being much longer than ours, soon came to our right flank and joined in a heavy fire.” Colonel Allen realized the position was untenable and ordered a retreat. The 154th was soon encircled, and the colonel gave the order for the men to run in order to avoid capture. Allen remembered, “we were compelled to cut our way through…in in doing so, our losses were heavy.” Of the 350 men of the 154th who were engaged that day, only eighteen succeeded in reaching Cemetery Hill.8

The Battle of Gettysburg continued for two more days, resulting in a Union victory – at heavy cost. On July 4, the day of the Humistons' ninth anniversary, the Confederate army retreated from town and the myriad dead from both sides were gathered. On that day the body of a soldier was discovered on the railroad tracks on Stratton Street. He had been shot through the lungs and had likely suffered many hours before expiring where he fell. He had no identification, except that he was clutching an ambrotype of three children in his hand. This father, knowing death was near, had taken out the image and looked at it one last time.

The story of the unidentified dead soldier clutching the photograph of his children soon made headlines. Newspapers and magazines published the picture, hoping to find the slain soldier’s identity. One of them was The American Presbyterian , a small circular with relatively few subscribers. One of their patrons was a woman living in Portville, New York. When she opened the magazine, she immediately recognized the photograph of the children. They were her neighbors, the Humistons.9

Philinda Humiston and her children became famous in their grief. Unable to afford the fee to bring her husband home for burial, Philinda received an invitation to come to Gettysburg. A new orphanage was established, and the citizens of Gettysburg hoped that the position would help Philinda keep her children with her, and allow them to remain close to Amos, who was buried in the Soldiers National Cemetery.

On Decoration Day in 1868, Philinda Humiston allowed the children of the orphanage to strew flowers on the graves of the Union dead on Cemetery Hill. Many of the orphans, including Frank, Alice and Frederick, placed bouquets on the tombstones of their own fathers.

One man’s untimely fate has brought a time-honored tradition to Gettysburg. Every year, on Memorial Day, children reverently place flowers on the graves of the Union dead. In this way, the terrible loss and sacrifice, will always be remembered.

The 154th New York, part of Colonel Charles Coster’s Brigade, were first deployed in the Evergreen Cemetery on Cemetery Hill south of town. The high command had noticed the hill and decided it was a good defensive position; however, the fight was still a few miles away to the west and, soon enough, included the north of town. As the battle worsened, and General Meade had not yet arrived, General Howard learned of the death of General Reynolds – the ranking commander on the field. Howard decided that “ the mighty panorama of war ” needed additional men at the front and sent Coster’s Brigade into battle. As the 154th rushed toward the fight, they saw their fellow soldiers already rushing back toward Cemetery Hill. The sight reminded them of Chancellorsville. Coster’s Brigade came too late to bolster the outnumbered Union troops, including men from their own corps.7

Had the 154th been at the front lines that day at Gettysburg, they might have had a chance to survive it. Instead, they were sacrificed for the sake of others’ survival. Near the railroad tracks in town, near Kuhn’s brickyard, the 154th made a valiant stand against a numerically superior enemy. Men from North Carolina and Louisiana crushed the battle line of the 154th New York. Lieutenant Colonel Allen, commander of the regiment, later recorded, “We were scarcely in position when the enemy, who were advancing in vastly superior numbers in our front, commenced the attack…We held the enemy in check…but their line of battle, being much longer than ours, soon came to our right flank and joined in a heavy fire.” Colonel Allen realized the position was untenable and ordered a retreat. The 154th was soon encircled, and the colonel gave the order for the men to run in order to avoid capture. Allen remembered, “we were compelled to cut our way through…in in doing so, our losses were heavy.” Of the 350 men of the 154th who were engaged that day, only eighteen succeeded in reaching Cemetery Hill.8

The Battle of Gettysburg continued for two more days, resulting in a Union victory – at heavy cost. On July 4, the day of the Humistons' ninth anniversary, the Confederate army retreated from town and the myriad dead from both sides were gathered. On that day the body of a soldier was discovered on the railroad tracks on Stratton Street. He had been shot through the lungs and had likely suffered many hours before expiring where he fell. He had no identification, except that he was clutching an ambrotype of three children in his hand. This father, knowing death was near, had taken out the image and looked at it one last time.

The story of the unidentified dead soldier clutching the photograph of his children soon made headlines. Newspapers and magazines published the picture, hoping to find the slain soldier’s identity. One of them was The American Presbyterian , a small circular with relatively few subscribers. One of their patrons was a woman living in Portville, New York. When she opened the magazine, she immediately recognized the photograph of the children. They were her neighbors, the Humistons.9

Philinda Humiston and her children became famous in their grief. Unable to afford the fee to bring her husband home for burial, Philinda received an invitation to come to Gettysburg. A new orphanage was established, and the citizens of Gettysburg hoped that the position would help Philinda keep her children with her, and allow them to remain close to Amos, who was buried in the Soldiers National Cemetery.

On Decoration Day in 1868, Philinda Humiston allowed the children of the orphanage to strew flowers on the graves of the Union dead on Cemetery Hill. Many of the orphans, including Frank, Alice and Frederick, placed bouquets on the tombstones of their own fathers.

One man’s untimely fate has brought a time-honored tradition to Gettysburg. Every year, on Memorial Day, children reverently place flowers on the graves of the Union dead. In this way, the terrible loss and sacrifice, will always be remembered.

The Memorial Day tradition continues

(Author photo)

Sources: Coddington, Edwin B. The Gettysburg Campaign: A Study in Command. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1968. Dunkelman, Mark H. Gettysburg’s Unknown Soldier: The Life, Death, and Celebrity of Amos Humiston. Westport, CT: Praeger Publishers, 1999. Fox, William. New York at Gettysburg. 3 Vols. Albany, NY: J.B. Lyon Co., 1902. Warner, Ezra. Generals in Blue: Lives of the Union Commanders. Baton Rouge and London: Louisiana State University Press, 1964. Official Report: Daniel B. Allen, 154

th

New York Volunteers Regimental File, Gettysburg National Military Park (hereafter GNMP).

Notes:

1. Dunkelman, p. 57.

2. Fox, vol. 3, p. 1054.

3. Dunkelman, p. 80.

4. Warner, pp. 233-234.

5. Warner, p. 234. Dunkelman, p. 81.

6. Warner, pp. 233, 317.

7. Fox, vol. 3, pp. 1049-1050. Coddington, p. 305.

8. Allen, Official Report, 154th New York File, GNMP.

9. Dunkelman, p. 90.

Notes:

1. Dunkelman, p. 57.

2. Fox, vol. 3, p. 1054.

3. Dunkelman, p. 80.

4. Warner, pp. 233-234.

5. Warner, p. 234. Dunkelman, p. 81.

6. Warner, pp. 233, 317.

7. Fox, vol. 3, pp. 1049-1050. Coddington, p. 305.

8. Allen, Official Report, 154th New York File, GNMP.

9. Dunkelman, p. 90.