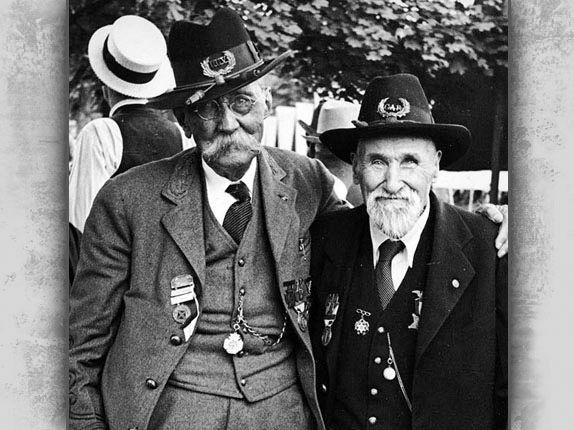

Two Civil War veterans at the Last Reunion

(National Park Service)

When Gettysburg’s Grand Reunion of 1913 drew to a close, many newspapers claimed it was “the Last Reunion of the Blue and the Gray”. They would be wrong.1

The state of Pennsylvania issued an invitation to the many veterans who attended the reunion during the summer of 1913 to return in twenty-five years for another, final, reunion at Gettysburg, in 1938. Most believed it would never happen, scoffing at the invitation as “impossible”, since the Civil War veterans were already elderly. As the years passed and the aged soldiers diminished to relatively few in number, the plans for that last reunion were nearly scrapped. One detractor explained that “there would be too few veterans left”. Additionally, those surviving veterans would be so aged – most of them drawing near the century mark – that they would be too feeble to attend.2

During the 50th Reunion in 1913, President Woodrow Wilson, who was the son of a Confederate veteran (and the first Southern President since Zachary Taylor occupied the White House in 1850), uttered a moving speech that stirred the souls of the participants. The sorrowful farewells that followed constrained the Pennsylvania Governor, John Tener, to issue an invitation to come back once more.

The ensuing twenty-five years almost prevented any hope of another reunion of the Blue and the Gray. The American involvement in World War I, the millions of deaths from the influenza epidemic, the passing of the last of the Union and Confederate generals (Felix Robertson from the South in 1928 and Adelbert Ames from the North in 1933), followed by the Great Depression all hampered the efforts of Pennsylvania’s attempts to keep their promise of another, final, reunion.

With the passing of their respective commanders, a new wave of separatist sentiment began to waft over the veterans’ organizations – the Grand Army of the Republic (GAR) and the United Confederate Veterans (UCV) began to divide themselves again in recalling the war of the ages. When the official invitation was extended in 1935, a disagreement erupted over whether or not the Confederate veterans could fly their flags at the reunion at Gettysburg. When told that they could not do so, the UCV commander, Harry R. Lee, deeply offended, told the organizers that they could “go to Hell.”3

It seems strange that a place like Amarillo, Texas – a town about as far from Gettysburg as one could get in the forty-eight contiguous states – would be the place where the 75th Reunion was secured. It was where Harry Lee lived, and it was there that Pennsylvania Governor George Earle sent his emissary, Paul Roy. The missive was a precise plea: “You brave and courageous men of the South, if you accept our sincere and cordial invitation and come to Gettysburg in 1938, you may fly your flags unfurled, as you wish.”4

Paul Roy, who served as the Executive Secretary of the Pennsylvania State Commission, and was the current editor of The Gettysburg Times, knew if he could convince Harry Lee to attend the reunion, the rest of the Confederate veterans would follow his lead.

Harry Lee was 87 years old in the summer of 1935 when he met with Paul Roy at a hotel lobby in Amarillo. He was a fiery gentleman with an intimidating presence, and his booming voice still made men cower. Mr. Roy stood quietly, facing the old commander. A crowd gathered around them, ominously quiet. Lee unloaded his angry protests to the tacit man from Pennsylvania, who patiently bore the rebuke. When the outburst ended, Mr. Roy read Governor Earle’s invitation. He then explained that in 1913, “John Tener, then Governor of Pennsylvania, invited the veterans to return in 25 years for a final reunion. Pennsylvania is now making good that invitation.” He added that this Last Reunion would be significant to history, and asked the Confederate leader to reconsider. Roy knew that if Lee walked away, the Last Reunion would go with him.5

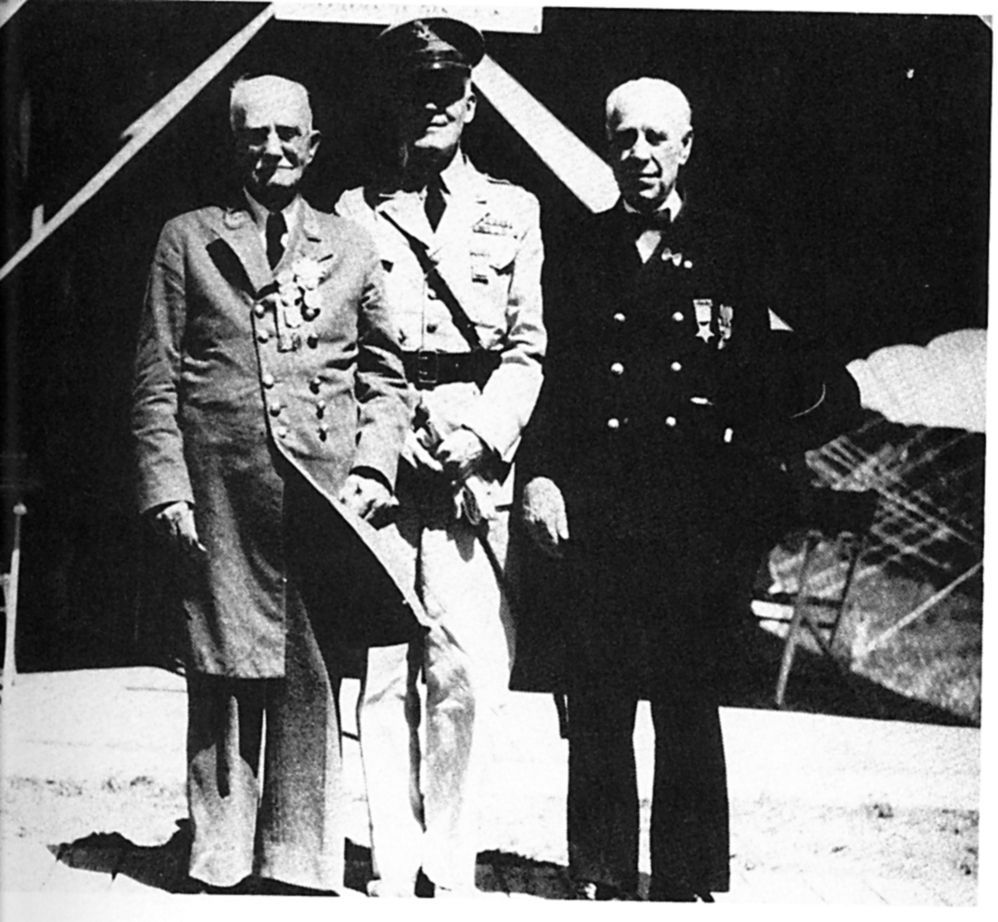

Commanders Claypool (l.) and Mennett (r.)

(National Park Service)

Even with Harry Lee’s endorsement, Roy still had hurdles to overcome. One evening, after addressing a United Confederate Veterans group in Jackson, Mississippi, several women blocked his way as he attempted to leave the building. They “started to harangue me,” Paul Roy recalled, “as a ‘damn Yankee’ who was ‘trying to kill our veterans’. Two women scratched my face and tried to tear my coat off, all the while shouting and shrieking unprintable accusations.” He managed to get away, escaping to the safety of his hotel room. Luckily, these types of issues were not common. Most people, north and south, experienced, “a surging wave of Reunion sentiment” and were excited about the 75th Anniversary of the Battle of Gettysburg. The Grand Rapids Press in Michigan printed that “the spirit of such a reunion will be the spirit of hate forgotten.” Another journalist wrote that “it appeared obvious that the bitterness and ill feeling, so long prevailing in the two veterans’ organizations had been…erased and dissipated.”7

The Last Reunion of the Blue and the Gray at Gettysburg took place from June 29 through July 6, 1938. There were 1, 845 Civil War veterans in attendance. About double that number of veterans still survived but due to advanced ages and long distances, they were unable to attend. Of those who attended the 75th anniversary reunion, 1359 were Union veterans and 486 were Confederate. Of the number, only sixteen were veterans of the Battle of Gettysburg – ten Union and six Confederate. The small percentage of Gettysburg survivors was a testament to the difficulty of that awful battle – as well as the ensuing conflicts of 1864, where many of the Gettysburg combatants were killed or severely wounded. To be able to attend the reunion as a former combatant of the war, each veteran had to provide papers to show the regiment of his enlistment and an honorable discharge. If these could not be provided, a signed affidavit from the governor of his state proved equally sufficient – which was sometimes the case with the Confederate veterans.8

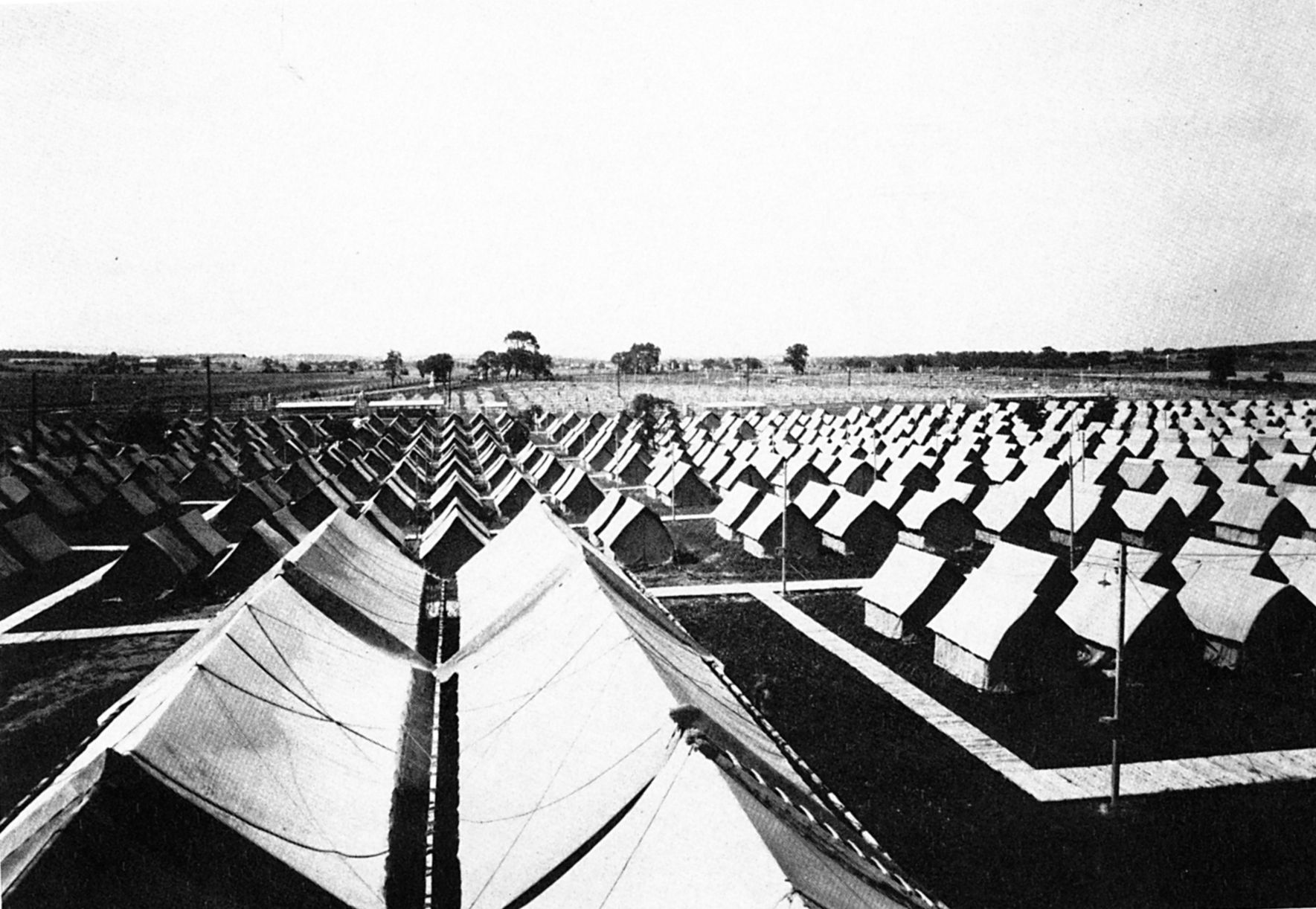

True to his word, Governor Earle permitted the Confederate veterans to fly their regimental flags in camp, which was created to be an enormous tent city on the northern fringe of town between Gettysburg College and Oak Ridge – both had been part of the first day’s battle. In addition to providing housing for the nearly two thousand veterans, the town supplied quarters for an equal number of family members who were needed to accompany the aged veterans. Doctors, Red Cross staff members, nurses, health department officials, cooks, bakers, and veterans of later wars who offered aid, sustenance, music and other entertainments for the aged soldiers were also housed there. The amazing tent city provided mess halls, hospitals, and a boardwalk to facilitate visitations. In all, the tent city provided quarters for nearly seven thousand people. The local Boy Scout organizations also furnished a scout escort for each veteran who attended.9

Sadly, Harry Lee was not one of them. The fiery Confederate commander died in Amarillo at age 90, just two months before the reunion took place. His last audible words were about the event he had helped to bring to pass: “I’m going to Gettysburg if they have to take me there on a stretcher.” He went on, no doubt to a far more glorious reunion.10

The High Water Mark, 1938

(National Park Service)

On June 29 they began to arrive, mostly by train. Annette Tucker, the wife of a Confederate veteran from Florida, remembered that the visiting began on the trains to Gettysburg. “All during the trip,” she said, “they were greeting each other, ‘Comrade, I’m glad to see you. Where are you from and how old are you now ?’” She recalled that almost all of the men were significantly advanced in age, most of them in their nineties. Quite a few had passed the century mark. The youngest, according to her, was Major General F.M. Ironman, who was purportedly the youngest at age 86. He had joined Lee’s army in 1865 at the age of 13. The eldest, a former Massachusetts infantryman and part of the U.S. Colored Troops, was the ripe old age of 107. Though a few others claimed to be older, they were unable to document their dates of birth.12

The opening ceremonies at Gettysburg College included a program where the commanders of the GAR and UCV joined Governor Earle in welcoming the troops to the famous battlefield. With Harry Lee’s death, the new leader of the United Confederate Veterans was John Claypool from St. Louis, Missouri. The Union Commander was Dr. Overton Mennett of Los Angeles, California.

In his opening speech, John Claypool took note of the benevolence that pervaded the troops. He then said, “When we consider the outcome of the great struggle of the American people, I say to you that the American people as a whole deserve a great honor…because of their manhood, and because of their spirit of reconciliation…This could only happen in the United American States.” He declared that the people of the South were Americans first, and for this reason they refused to continue the fight after Appomattox. “There would have been guerilla warfare going on in this country to this very day, but the Southern people possessed too much Americanism for anything of that kind to happen.”13

Dr. Overton Mennett remarked, “Those of us who remember this place so well are old, and the passing years have brought tolerance and forgiveness. The wounds are healed and it is our fervent hope that, with our passing, not even a scar will remain.”14

Programs, honorary tributes, a parade and a special dedication of a new monument continued through the next several days as the veterans mingled with the succeeding generations and each other. On Saturday, July 2, a parade honoring the veterans marched through downtown Gettysburg. According to one observer, it “was the largest and most colorful parade in the historic town of Gettysburg.” The seven-mile procession began at 1:30 p.m. and lasted for over two hours. Marching bands, current troops and more recent veterans, local and state dignitaries, and those Civil War soldiers who were able to walk in the parade were all included.15

Later that evening, veterans of World War I paid homage to the old troops at Gettysburg College. There was a special performance by the United States Marine Band. They ended the night with a special rendition of Taps by four buglers: Two were in the cupola at Old Dorm, one stood on Oak Ridge, and the other stood near the crowd at the college.16

The later generations thought the evening’s performance a surreal experience to listen to “the songs of long ago”. From the “hymns to the Iowa Corn Song to Dixie – we sang them all.” At one point, Dr. Mennett offered a solo of Tenting Tonight – the bivouac song of the Civil War. The audience was delighted, and the veterans were visibly moved.17

The Eternal Light Peace Memorial

(Author Photo)

On Sunday, July 3, the few surviving Gettysburg veterans stood near the Angle at Cemetery Ridge to shake hands at the High-Water Mark. Twenty-five years earlier the veterans had reenacted Pickett’s Charge and had run toward the wall. In 1938, only one Confederate veteran who had been in the famous charge was left with, accompanied by a handful of Union combatants. O. Richard Gellette from Joe Davis’s Brigade shook hands with his former foes in blue across the wall.

Gellette, who was 17 years old at the Battle of Gettysburg, spoke to many of his recollections of that fateful day in 1863. “I was young, but I was as big as any man,” he said. “The field in front of us looked like ploughed ground where the shells hit. The corn was knee-high. We went up the hill [Cemetery Ridge] but we couldn’t stay there.”18

To 14-year-old Chuck Caldwell, Gelette explained that when the Union cannon opened up on the advancing Confederates, “the men fell in piles. I crouched down behind one of the piles” in an attempt to stay alive. He had meant to continue the advance when the leaden storm abated enough to allow him forward, “but it never did”. By the time the firing stopped, Pickett’s Charge had ended.19

At the wall, one of the Union veterans said to Gellette, “You old Johnny! You look like the fellow who shot me, but it’s all right now.”20

One spectator at the High-Water Mark mentioned that he heard the rebel yell. “It was very high pitched,” he remembered, “long and loud

.

”21

At 6:30 p.m. on July 3, the Eternal Light Peace Memorial was dedicated on Oak Hill, where the First Day’s battle had occurred. A crowd of over 200,000 people attended, standing on the fields beneath the hill like a phalanx of troops in intense heat. The Civil War veterans were seated at the base of the memorial, covered at the time by the 48-starred United States flag. They were divided only by the sidewalk.

President Franklin D. Roosevelt, who arrived at the dedication in a convertible, stood on a patriotically festooned platform, and gave the dedicatory speech. “Men who wore the Blue and men who wore the Gray are here together,” he said, “a fragment spared by time. They are brought here by the memories of old…All of them we honor, not asking under which flag they fought then – thankful that they stand together under one flag now.” 2

At the conclusion of FDR’s speech, two veterans, one Union and one Confederate, unveiled and lit the Eternal Light Peace Memorial. The base of the monument is Maine granite, and the shaft is limestone from Alabama – representing North and South, united in peace. Etched on the base are the words “Peace Eternal in a Nation United”. Atop the memorial is a bronze urn, where the first Eternal Flame was ignited on that day in 1938.

The cheers of the crowd echoed for many miles as the meaning of the memorial reverberated across the years. “For the issue,” Roosevelt stated, “ will be the continuing issue before the nation so long as we cling to the purposes for which the nation was founded.” That same issue was expressed by Abraham Lincoln nearly 75 years earlier in his Gettysburg Address. It symbolizes liberty, justice for every citizen, and unity. It is a perpetual reminder – and choice – for each successive generation.23

At the end of the dedication, the crowd was entertained by an aerial demonstration. The maneuvers continued until dusk.

Between the events, the aged soldiers simply visited with each other. “Once again, they hailed each other as ‘Johnny Reb’ and “Damn Yankee’, but here was never rancor in the quivering words.”24

Colonel Jacob M. Sheads remembered, “When speaking with the Union veterans, you had better be sure to mention the glorious Union. While talking with Confederate veterans, you made sure to speak of Robert E. Lee.

”25

Chuck Caldwell, who in later years fought as a Marine at the Battle of Guadalcanal, interviewed several of the veterans, including Albert Woolson, the last officially recognized survivor of the Civil War.

The Tent City, 1938

(National Park Service)

In one of the mess halls, a Georgia veteran remarked to one of the World War I veterans that, “We have broken bread together here. I don’t call this a meal. It is a sacrament.” A journalist from New Mexico echoed the sentiment: “Gettysburg is…twice hallowed since the Gray and the Blue have clasped hands on those sanguinary fields.”27

George Chumley, a veteran of the 4th Alabama regiment which fought at Gettysburg, said to a journalist, “I thank God that time has healed our passions and love does abound.”28

Seymour Ward, a veteran of the 104th Ohio, said, “I express gratitude to the great state of Pennsylvania for what they are doing for us old boys before we are called away to the great camping ground.”29

Charles Long, a Confederate veteran from Florida, wrote, “I enjoyed the Blue-Gray reunion supremely on account of the main fundamental purpose of it. One flag, one people in unity. UNION.”30

While the hosts of the reunion had planned for every contingency, there were nevertheless a few scares. Several of the veterans, due to their advanced age, the July heat, and the activities – strenuous for many – fell ill. Six were placed in the hospital and one of them, 91-year-old John Carpenter of Florida, was the victim of a heart attack. He died on July 5, just before the last day of the reunion.31

The tent city was immense and the streets appeared nearly identical, so some veterans became disoriented. A young girl lost her grandfather while she made the cots one morning. After searching for him, she entered the tent of Mary Phillips, the wife of a Confederate veteran. In tears, the girls asked for her help, and soon an extensive search was underway. Mrs. Phillips recalled, “After a long search, he was found asleep in one of the empty tents.”32

On Monday, July 4, the veterans watched a series of military drills and tank demonstrations. At nine p.m., a massive fireworks display for Independence Day took place on Oak Ridge, easily visible from just outside their tents. After the fireworks, the old veterans sang their bivouac favorite from the war, Tenting Tonight on the Old Campground. It was the last time the song was sung by such a large gathering of Civil War veterans.33

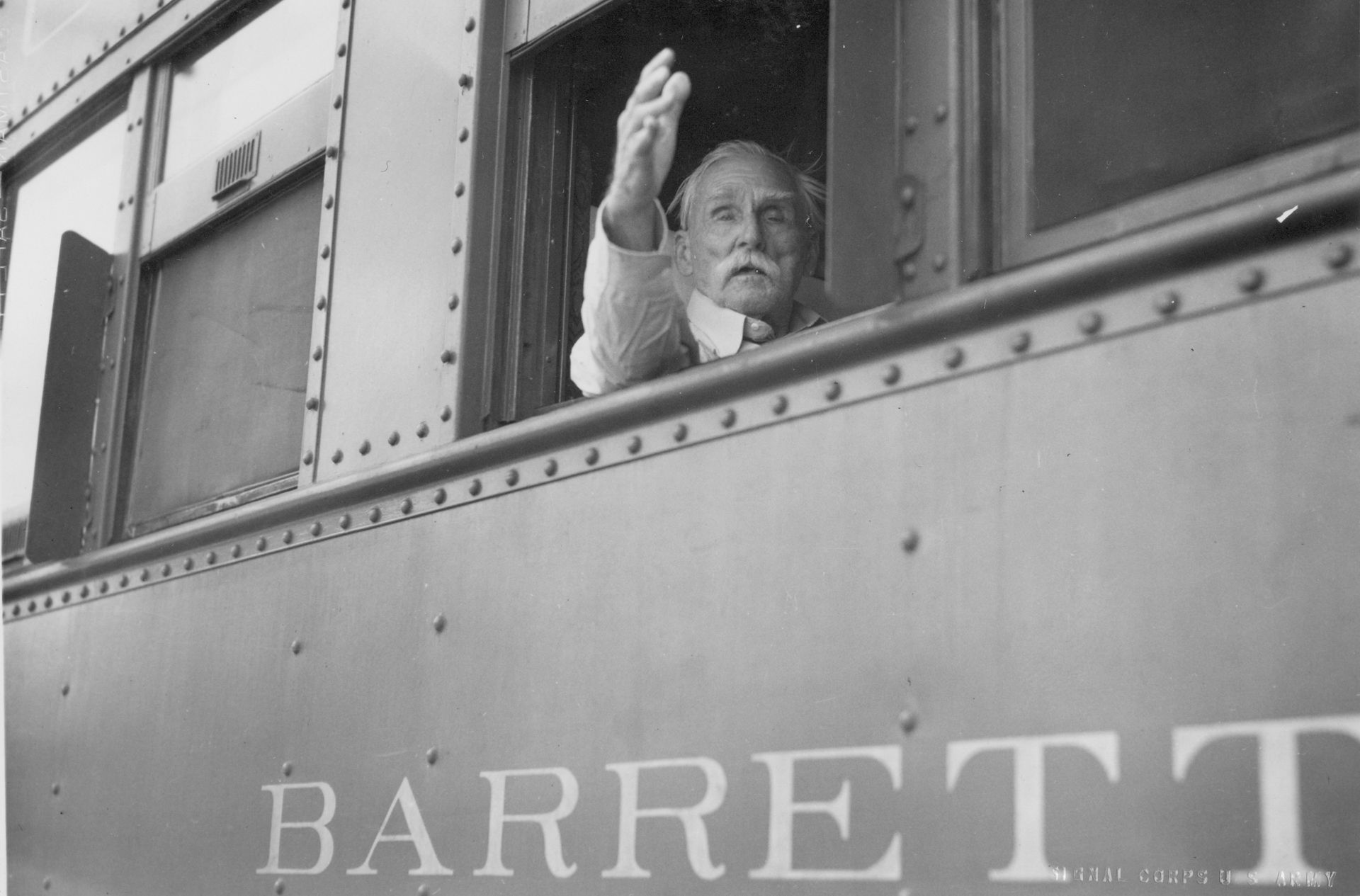

On Tuesday, July 5, many of the old veterans began to leave. By July 6, the final train pulled away from Gettysburg, carrying the last of the veterans. Sadly, six of them died on the journey home.34

The Last Goodbye

(Adams County Historical Society)

“There was no rancor or bitterness among those old veterans,” Colonel Sheads remembered. “It was all benevolence and kindness. They didn’t have any bad feelings – not one of them.”36

“We were proud we were Americans,” Annette Tucker explained. “I am sure that many like myself rededicated their lives to the service of their country.” An Oklahoma spectator agreed. “Their heroism remains a great American heritage.”37

The eternal flame lit those many years ago at the memorial on Oak Hill still shines. With that memory, the echoes of the Last Reunion can be summed up by the words of Harry Lee to Paul Roy that day in Amarillo: “We should be friends.”

Sources: The 75 th Anniversary Participant Accounts, Folders #1 and #2, Gettysburg National Military Park (hereafter GNMP). The 75 th Anniversary File, Adams Cunty Historical Society (hereafter ACHS). Barraco, Angelo. “The 75th Reunion”. Unpublished manuscript, GNMP. Author interview with Churck Caldwell (1923-2017), June 5, 1998. Author interview with Colonel Jacob M. Sheads (1910-2002), May 12, 1998. Cohen, Stan. Hands Across the Wall: The 50th and 75th Reunions of the Gettysburg Battle . Charleston, WVA: Pictorial Histories Publishing Co., 1982. Daniel Dougherty Account, 75 th Reunion Folder #2, GNMP. Phillips, Mary. “Eight Days in a Tent.” Folder #1, GNMP. Letter, Charles Long to Mary Phillips, Folder #1, GNMP. Roy, Paul. The Last Reunion of the Blue and the Gray . Vol. IV. Gettysburg, PA: Copyright by Paul Roy, 1950. Copy, GNMP. Roy, Paul. Pennsylvania at Gettysburg: The 75th Anniversary . Volume 4. Reference copy, GNMP. William Sprinkle Account (1926-1996), Folder #2, GNMP. Tucker, Annette. “The Last Reunion.” Unpublished account, Folder #1, GNMP. The Albuquerque Journal, July 1, 1938. “The Last Reunion”, The Gettysburg Times, July 6, 1938. The Grand Rapids Press, July 2, 1938. The Tulsa World, July 4, 1938. The Washington Star, July 5, 1938.

End Notes:

1. The Gettysburg Times, July 6, 1938. 75

th

Reunion File, ACHS.

2. Ibid.

3. Roy, The Last Reunion

, p. 43.

4. Ibid.

5. Ibid, p. 45.

6. Ibid.

7. Roy, The Last Reunion

, p. 27. The Grand Rapids Press, July 2, 1938.

8. Folder #1, 75

th

Anniversary Participant Accounts, GNMP.

9. Ibid.

10. Roy, The Last Reunion

, p. 58.

11. Cohen, p. 40.

12. Tucker, “The Last Reunion”, p. 3. Cohen, p. 56.

13. Roy, The Last Reunion

, p. 99.

14. Ibid. p. 98.

15. The Gettysburg Times, July 6, 1938.

16. Tucker, “The Last Reunion”, p. 10.

17. Ibid.

18. The Gettysburg Times, July 6, 1938.

19. Caldwell, June 5, 1998.

20. The Washington Star, July 5, 1938.

21. William Sprinkle Account, Folder #2, GNMP.

22. The Gettysburg Times, July 6, 1938.

23. Roy, The Last Reunion

, p. 103.

24. The Tulsa World, July 4, 1938.

25. Sheads, May 12, 1998.

26. Caldwell, June 5, 1998.

27. The Washington Star, July 5, 1938. The Albuquerque Journal, July 1, 1938.

28. The Washington Star, July 5, 1938.

29. Ibid.

30. Phillips, p. 8.

31. Barraco Account, “The 75

th

Reunion”, GNMP.

32. Phillips, p. 9.

33. Roy, Pennsylvania at Gettysburg/The 75

th

Anniversary

, p. 436.

34. Sheads, May 12, 1998.

35. Dougherty Account, Folder #2, GNMP.

36. Sheads, May 12, 1998.

37.Tucker, p. 12. The Tulsa World, July 4, 1938.