They Survived Gettysburg (But Not the War)

by Diana Loski

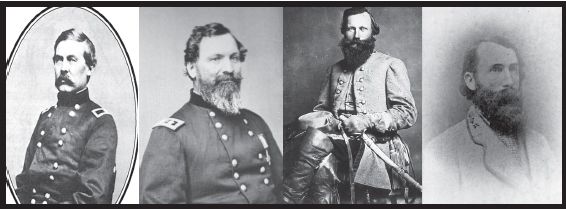

(l. to r.) Generals Buford, Sedgwick, Stuart & Hill (Library of Congress)

At the Battle of Gettysburg, thirty-four men who held the rank of general officer fell as casualties in that conflict – but many of those survived their wounds. There were many more who fought through the epic battle without becoming a casualty, but nevertheless did not survive the war. Here are ten of those commanders, North and South, who survived Gettysburg unscathed, only to perish later in the war.

John Buford (USA) was the Kentucky-born horseman who served as a division commander in the Federal cavalry at Gettysburg. It was Buford who orchestrated the beginning of the battle on July 1, 1863. After the guns grew silent at Gettysburg, Buford and his men were busy chasing General Lee and his army all the way to the Potomac. They managed to capture five hundred Confederates before Lee and his men could cross the river at Williamsport, Maryland.

In the autumn during the Mine Run campaign, Buford’s health began to fail. The changeable weather and endless hours in the saddle wore him down. Suffering from typhoid fever, rheumatism and exhaustion, Buford kept up his relentless schedule until he was so ill he was taken to Washington to recuperate. Once at the home of his friend and fellow cavalry general George Stoneman, Buford contracted a terminal case of pneumonia. Close friends were summoned, and Buford’s wife quickly attempted to make the trip to the capital, although she did not reach her husband in time. Buford died on December 16, 1863. Upon his deathbed he learned he had received a brevet to Major General for gallantry at Gettysburg. When Buford heard of his promotion, he sighed and said, “It is too late. Now I wish I could live.”1

Buford was beloved by his division. Their esteem of the great general is made evident by his tombstone at West Point, a 20-foot-high, decorative obelisk, all paid by donations from his men.

James Wadsworth (USA) was just a few months younger than Robert E. Lee, born in October 1807. At Gettysburg he served as a division commander in the Federal First Corps, leading a stiff resistance to the Confederate onslaught west of town on July 1, 1863. A New York native, Wadsworth was wealthy from a young age and gave liberally to the less fortunate. Disgusted by the institution of slavery, he wished to see it expunged forever – and readily offered his services to the Union at the start of the war in spite of his advanced age. He was so well liked and so widely known that he was nominated for governor of New York in 1862. He remained in the field during the campaign, and lost by a narrow margin.

In spite of his wealth, he lived in the same meager conditions as his men and ate what they were given.

At the Battle of the Wilderness, on May 6, 1864, Wadsworth was leading a division of the Federal Fifth Corps when he was shot in the head. He never regained consciousness. One of the men of his division eulogized him by saying, “He was the truest and most thoroughly loyal American I ever knew.”2

John Sedgwick (USA) was considered by many to be the most beloved general officer in the Union army. He was affectionately dubbed “Uncle John” by his men. Born in Connecticut in 1813, Sedgwick graduated from West Point in 1837, along with future generals Jubal Early, Joe Hooker, and Braxton Bragg. He fought in the Mexican War, and when the Civil War erupted less than two decades later, he immediately offered his services to the Union. He had risen to the rank of commander of the Federal Sixth Corps by the time of the Battle of Gettysburg. His troops were the last to arrive on the side of the Union, and were placed in reserve. On the third day, Sedgwick’s troops defended Little Round Top – but the Confederates instead attacked the Federal right (Culp’s Hill) and later the center (Pickett’s Charge) on that day.

In 1864 President Lincoln appointed Ulysses S. Grant as commander-in-chief of all Union armies. Grant insisted that defeating Lee and his army as the focus of winning the war, and embarked on the Overland Campaign, which resulted in the battles at The Wilderness, Spotsylvania, and Cold Harbor before reaching Petersburg.

The Battle of the Wilderness in northern Virginia resulted in a stalemate, with Grant immediately pursuing the elusive Lee a few miles toward Spotsylvania Court House. In a position that came to be known as The Bloody Angle at Spotsylvania, Sedgwick, in charge of troops deployed there, was displeased with the positioning of the artillery. Moving to direct the big guns, he saw men ducking and hiding from the whistling bullets from distant Confederate sharpshooters. “What?” he said, “Men dodging this way for single bullets? What will you do when they open fire along the whole line? I am ashamed of you.”

When the general’s chief of staff begged Sedgwick to go to the rear, the general scoffed and said, “They couldn’t hit an elephant at this distance.” Before he finished the sentence, a bullet struck him below the left eye. He died almost instantly.

General Grant was distressed to learn of the death of General Sedgwick. He claimed that losing Sedgwick was as disastrous as losing an entire division. General Meade wept at the news. Even Robert E. Lee, who had known Sedgwick during the War with Mexico, was saddened to hear of his passing.3

Alexander Hays (USA) was a Pennsylvania native of Irish descent, who graduated from West Point in 1844. One of his closest friends was fellow cadet Ulysses S. Grant, who graduated one year earlier. Filled with ire at the Confederate invasion of his home state in 1863, Hays fought with fervor at the Battle of Gettysburg, where he commanded a division of the Federal Second Corps. A statue of the intrepid general stands at Ziegler’s Grove on Cemetery Ridge, where the general fought against Pickett’s Charge.

With the loss of so many men of the Federal Third Corps due to the disobedience of their commander Dan Sickles at Gettysburg, the survivors were absorbed into the Federal Second and Fifth Corps. One of Sickles’ division commanders, David Birney, outranked Hays. As a result, Birney was given command of Hays’ division, and Hays was relegated to brigade command in 1864. Hays was leading his brigade at The Wilderness on May 5, 1864 toward the crossroads of the Orange Plank Road and Brock Road, when a sniper’s bullet struck Hays in the head. He was killed instantly. The 44-year-old was awarded the brevet of Major-General, albeit posthumously.4

David Birney (USA) was born in Alabama, the son of an ardent abolitionist. Moving to Cincinnati as a youth, Birney moved to Philadelphia to study law. He became a longtime friend of politician Dan Sickles, under whom Birney served at Gettysburg.

Though not a West Point graduate, Birney was nevertheless fascinated with military tactics and intensely studied the subject. When the Civil War burst upon the broken nation, Birney immediately offered his services to the Union and began the war as the lieutenant-colonel of a Pennsylvania regiment. He rose through the ranks to being in command of a division in Dan Sickles’ Federal Third Corps. When Sickles was wounded at Gettysburg, Birney served as the Third Corps commander for a brief time. Though Sickles’ unwarranted move to the Peach Orchard caused an understandable stir, Birney managed to acquit himself of any disobedience and error. As the Federal Third Corps ceased to exist after Gettysburg, he was given a division in the Second Corps. At Petersburg, Birney was promoted by General Grant to command the Federal Tenth Corps. Birney, however, was not able to enjoy the new command. He fell ill that July with malaria – a common ailment in camps in the South at the time – and was sent home to Philadelphia to recuperate. He never recovered, and died on October 18, 1864. Dan Sickles was one of the many mourners at his funeral.5

James Ewell Brown Stuart (CSA) remains one of the best remembered generals of the Civil War. Dashing and fearless, the youthful Virginian was a capable fighter – often riding around the Union army, capturing supplies and soldiers. Stuart ably took command of General Jackson’s infantry corps after the former leader was mortally wounded and his second in command, A.P. Hill, was also wounded. At Gettysburg, Stuart was tardy in his arrival, having been prevented by Union cavalry to reach General Lee with his information on the position of the Union army. Some historians blame Stuart for causing the unexpected fight in Pennsylvania but Lee quickly forgave him. At Gettysburg on East Cavalry Field, Stuart fought a significant battle against Union cavalry. The event, however, remains largely overshadowed by Pickett’s Charge, which occurred at approximately the same time.

In 1864, when General Grant headed the Army of the Potomac as commander of all Union armies, Stuart, who commanded Lee’s cavalry, was determined to raise havoc with the Federal forces. As the bulk of the Union troops fought at Spotsylvania, a portion of General Sheridan’s cavalry rode toward Richmond. In an attempt to thwart their advance, General Stuart met them at a place called Yellow Tavern. Stuart was easily recognized by his large plumed hat, and one of the Union cavalrymen took aim at the commander. Stuart was shot in the stomach, and the wound was mortal. Abdominal wounds are among the most painful, and the doctor attending the young general in his last hours urged him to drink whiskey to deaden the pain. Stuart refused. He had promised his mother he would never touch spirits, and remained true to the promise in his final hours. Stuart died the next day at the age of 33. He is buried in Hollywood Cemetery in Richmond.6

A.P. Hill (CSA) was one of the most colorful of the Confederate generals. He deliberately wore a red shirt in battle so that the opposing Federals could easily distinguish him. A graduate of West Point in 1842, “Little Powell” served in the Mexican War with distinction. Unlucky in his first serious courtship with the popular Ellen Marcy, Hill lost her to his friend George McClellan. During the Seven Days Battles in the spring of 1862, Hill gave the Union forces such a pounding that many of the men in blue, under McClellan’s command at the time, lamented that Mrs. McClellan should have married A.P. Hill instead.

At Gettysburg, General Hill was a new corps commander, but he was unable to lead his men personally due to an intense migraine headache. He also suffered from gonorrhea – the price he paid from a dalliance when a cadet at West Point. It was A.P. Hill’s corps that first engaged Buford’s cavalry west of Gettysburg on the morning of July 1, 1863. Those who survived the first day’s battle joined Pickett in his fateful charge on July 3.

General Hill continued to fight ably and courageously throughout the remainder of the war. With the fall of Petersburg on April 2, 1865, Hill remained with the rear guard of the army as General Lee vacated the city in an attempt to reach Joe Johnston’s troops in North Carolina. While attempting to ride to his men near Petersburg, a sniper’s bullet struck the general in the heart, killing him instantly. Like his compatriot Jeb Stuart, A.P. Hill is buried in Hollywood Cemetery.7

Stephen Dodson Ramseur (CSA) was the youngest general in the Confederacy, attaining that rank at age 27. A North Carolina native, the skilled Ramseur “could handle troops better than any other officer.” A West Point graduate in 1860, he offered his services to the Confederacy before his home state seceded. He began his tenure with the artillery, but was soon transferred to command infantry as the loss of commanders took its toll. Ramseur was wounded at Malvern Hill and Chancellorsville, but was sufficiently healed in time to fight at Gettysburg. As a brigadier general in Robert Rodes’ Division, Ewell’s Corps, Ramseur fought at the northwestern edge of town on the first day of the fight. He was notably calm in battle, but afterwards often wept over the losses of the men he led.

At the Battle of Gettysburg Ramseur was seen chasing Union soldiers through the town after the fight on the first day ended in what would be a pyrrhic victory for Lee’s army. He saw no further action in Pennsylvania.

After Gettysburg, Ramseur managed to obtain a furlough and returned to North Carolina to marry his sweetheart. By the following spring, he learned that he was going to be a father.

Ramseur was ill during the battle at The Wilderness, the result of dwindling, poor-quality rations among the men.

In the fall of 1864, Ramseur learned that his son was born. He asked for permission to return home to see his child. Lee told him that he was needed at an approaching battle, and then he could return home on furlough to see his family.

The battle of Cedar Creek took place in northern Virginia in mid-October 1864. As Sheridan’s cavalry faltered before the stiff resistance of the Confederate troops, Ramseur called to his men to drive the Union forces. He then turned to General John Gordon and remarked, “Well, General, I shall get my furlough today.” He was shortly afterward shot through both lungs from a Union bullet. As they saw their commander fall, the Confederates retreated, and Ramseur was left as a prisoner of war.8

One who visited Ramseur during his final hours was his former classmate at West Point, George Armstrong Custer. As Ramseur was unable to write, Custer allowed one of the Confederate prisoners to pen a letter to Mrs. Ramseur, telling her of her husband’s passing. Ramseur died the next day, October 20, 1864, just eight days shy of his first anniversary.

Junius Daniel (CSA) graduated from West Point in 1851, and as a result became a Confederate commander early in the Civil War. Born in North Carolina, he served in the Federal army on the frontier for seven years. In 1858 he resigned from the army to oversee his father’s plantation in Louisiana. He was living there when the war came. He first commanded the 14th North Carolina Infantry, then was promoted to brigade command over his fellow Tarheels in September 1862.

When the death of General Jackson after the Battle of Chancellorsville necessitated a reorganization of Lee’s army, Daniel and his brigade transferred to the Army of Northern Virginia. They proved an asset to the Confederate forces at Gettysburg. Daniel’s West Point training proved invaluable at Gettysburg, as his brigade grappled with men from both the Federal First and Eleventh Corps during the afternoon of the First Day. They also fought on Culp’s Hill on July 3. When the latter fight ended, one of Daniel’s staff noticed a large bullet hole in the general’s hat, just an inch above his forehead. Daniel removed the hat, looked at the hole and succinctly said, “Better there than an inch lower.”

His luck ran out at Spotsylvania, where a Union minié ball at the Bloody Angle found its mark. He was just a few weeks shy of his 36th birthday.9

Carnot Posey (CSA) was a lawyer and plantation owner from Woodville, Mississippi. Born in 1818, he fought in the War with Mexico with the rank of lieutenant in the 1st Mississippi Rifles regiment – led with distinction at Buena Vista by their commander Jefferson Davis. After the conflict with Mexico, Posey returned to the practice of law. In 1857 he was appointed by President Buchanan as the U.S. District Attorney for the District of Mississippi. He was serving at this office when war erupted, and he resigned to offer his services to the Confederacy. He began the war by serving as the colonel of the 16th Mississippi Infantry, and fought at First Manassas and Ball’s Bluff. He fought during the Peninsula Campaign and was promoted to brigadier general in late 1862. Posey’s brigade was part of General Richard Anderson’s Division at Gettysburg. As Confederate records are sketchy, it is unclear where Posey was during much of the fighting. While it appears that some of Anderson’s Division participated in Pickett’s Charge, Posey and his brigade did not cross the field of fire that day.

While Generals Meade and Lee did not officially plan to fight a battle again until The Wilderness in early May 1864, there was a campaign underway in the fall of 1863 called Mine Run. There were several skirmishes and conflicts during those days, with both armies on the move. General Lee saw an opportunity in mid-October that year as Meade’s army attempted to move around hilly terrain just southwest of Washington in northern Virginia. The result was called the Battle of Bristoe Station. The Union forces involved managed to elude and subdue the attacking Confederates, and a Union victory was achieved. Over a thousand Confederates fell in the attempt, including General Posey, who received a severe wound in his left thigh. Posey was taken to Charlottesville to convalesce.

At first it appeared that the general would recover from his wound, but infection set in, and Posey died a month later, on November 13, 1863. He is buried at the University of Virginia in Charlottesville.10

Sources: John Buford Participant Accounts File, Gettysburg National Military Park. Coddington, Edwin B. The Gettysburg Campaign: A Study in Command. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1968. Evans, Clement A. Confederate Military History Vol. IX, Richmond, VA: Confederate Publishing Company, 1899. Foote, Shelby. The Civil War: A Narrative. Vol. 2: “Fredericksburg to Meridian”. New York: Random House, 1963. Foote, Shelby. The Civil War: A Narrative, vol. 3: Red River to Appomattox. New York Random House, 1974. Gallagher, Gary. Stephen Dodson Ramseur, Lee’s Gallant General. Chapel Hill, NC: The University of North Carolina Press, 1985. Gordon, John B. Reminiscences of the Civil War. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1903 (reprint: TimeLife Books, 1981). Knoop, Jeanne. I Follow the Course, Come What May: Major General Dan Sickles USA. New York: Vantage Press, 1998. New York State Monuments Commission: In Memoriam: James S. Wadsworth. Albany, NY: Published by the State of New York, J.B. Lyons Company, 1916 (reprint, Benedum Books, 2003). Pfanz, Harry W. Gettysburg: The First Day. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2001. Plaster, Major John L. Sharpshooters in the Civil War. Boulder, CO: Paladin Books, 2009. Warner, Ezra J. Generals in Blue: Lives of the Union Commander. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1964. Warner, Ezra J. Generals in Gray: Lives of the Confederate Commanders. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1959.

End Notes:

1. John Buford Participant Accounts File, GNMP.

2. New York State Monuments Commission, Wadworth in Memoriam, p. 80. Coddington, pp. 268, 431.

3. Plaster, p. 117. Foote, vol. 3, p. 203.

4. Foote, vol. 3, p. 163. Coddington, p. 514. Warner, Generals in Blue, p. 224.

5. Coddington, pp. 397, 400. Warner, Generals in Blue, p. 34. Knoop, p. 100.

6. Warner, Generals in Gray, p. 296. Coddington, p. 198. Foote, vol. 2, pp. 231-232.

7. Pfanz, pp. 38, 116. Coddington, p 315. Warner, Generals in Gray, p. 135.

8. Gallagher, p. 17. Pfanz, p. 190. Coddington, p. 293. Gordon, p. 327.

9. Coddington, pp. 21, 290. Warner, Generals in Gray, 67. Pfanz, p. 213.

10. Evans, p. 265. Foote, vol. 2, pp. 517, 793. Warner, Generals in Gray, pp. 244-245.